![]()

Narsarsuaq Greenland: Our Sixth Destination Fuel Stop

![]() When I got up in the morning I wasn't feeling too bad. The excitement of

the upcoming flight carried me over any rough spots cause by shortage of

sleep. Besides, we had had a good rest in Scotland before heading out.

Despite the good weather report of the previous day, the new forecast

wasn't as optimistic. A warm front was pushing up from the south,

threatening to cut us off with fog, freezing drizzle, and later freezing

rain. With no icing protection other than our pitot heat, we could not

move with known icing. The young dispatcher, however, figured we could

beat the system before it socked in, and that was all the encouragement we

needed to continue.

When I got up in the morning I wasn't feeling too bad. The excitement of

the upcoming flight carried me over any rough spots cause by shortage of

sleep. Besides, we had had a good rest in Scotland before heading out.

Despite the good weather report of the previous day, the new forecast

wasn't as optimistic. A warm front was pushing up from the south,

threatening to cut us off with fog, freezing drizzle, and later freezing

rain. With no icing protection other than our pitot heat, we could not

move with known icing. The young dispatcher, however, figured we could

beat the system before it socked in, and that was all the encouragement we

needed to continue.

![]() We took

all the fuel we could muster for the longest segment of our TransAtlantic,

and headed out. Naturally we had a head wind, and a strong one at that.

The winds were forecast at 50kts, and they were all of that as we watched

the winds whip the ocean below into a frenzy. As we flew passed Keflavik,

we watched and heard a Danish registered Dash-7 take off toward the same

destination as us. Stretching the limits of syncronicity we figured since

he was a de-Havilland and we were a de-Havilland then it only made sense

that he would share some common bond and prove to be very helpful in

getting us weather and giving us pireps, especially concerning freezing

rain. Wrong!

We took

all the fuel we could muster for the longest segment of our TransAtlantic,

and headed out. Naturally we had a head wind, and a strong one at that.

The winds were forecast at 50kts, and they were all of that as we watched

the winds whip the ocean below into a frenzy. As we flew passed Keflavik,

we watched and heard a Danish registered Dash-7 take off toward the same

destination as us. Stretching the limits of syncronicity we figured since

he was a de-Havilland and we were a de-Havilland then it only made sense

that he would share some common bond and prove to be very helpful in

getting us weather and giving us pireps, especially concerning freezing

rain. Wrong!

![]() The pilot

wouldn't give us the time of day and would not even acknowledge our calls.

We ended getting help from a loud mouth Texan ferrying a Rockwell

Commander across the "Pond." He informed us that the freezing

drizzle started at the 10,000ft level and was very light. He punched

through and got on top at 12,000ft in a few minutes. Klaus voted that we

do the same.

The pilot

wouldn't give us the time of day and would not even acknowledge our calls.

We ended getting help from a loud mouth Texan ferrying a Rockwell

Commander across the "Pond." He informed us that the freezing

drizzle started at the 10,000ft level and was very light. He punched

through and got on top at 12,000ft in a few minutes. Klaus voted that we

do the same.

![]() Klaus even

joked about how I should not worry as we had our supplementary oxygen. His

theory of oxygen was that because he was a heavy smoker, (which, much to

his credit, he never smoked in the aircraft once; partly because of his

courtesy toward me, and partly because of his fear of blowing the ferry

fuel tanks that filled the cabin and prematurely ending our journey,) and

I never smoked, that he could tough it out without oxygen while I had to

wimp it out with my mask on at anything approaching 10,000ft. Up to this

point it appeared to be the truth.

Klaus even

joked about how I should not worry as we had our supplementary oxygen. His

theory of oxygen was that because he was a heavy smoker, (which, much to

his credit, he never smoked in the aircraft once; partly because of his

courtesy toward me, and partly because of his fear of blowing the ferry

fuel tanks that filled the cabin and prematurely ending our journey,) and

I never smoked, that he could tough it out without oxygen while I had to

wimp it out with my mask on at anything approaching 10,000ft. Up to this

point it appeared to be the truth.

![]() Well, I

decided that after crossing half the world, I was not going to miss out on

seeing the incredible Greenland glacial ice-cap for myself. To stay visual

would mean VFR below the cloud layer. Somewhere in the fog of the previous

night the Twin Otter, expert-of arctic-glacial-flying, pilot had told me

that whenever you get a warm front and the cloud comes down across the

glacier it will always leave a couple hundred foot layer of clear air

beneath. Something to do with cold heavy air laying on the surface

prevents the warm air from subsiding past the compression point or some

such nonsense. At the time, around mid-night, the theory sounded fine. I

was going to find this layer and VFR it across the ice-cap. I had done

this many times in the Rockies so why not here? Klaus was not happy, but I

was determined.

Well, I

decided that after crossing half the world, I was not going to miss out on

seeing the incredible Greenland glacial ice-cap for myself. To stay visual

would mean VFR below the cloud layer. Somewhere in the fog of the previous

night the Twin Otter, expert-of arctic-glacial-flying, pilot had told me

that whenever you get a warm front and the cloud comes down across the

glacier it will always leave a couple hundred foot layer of clear air

beneath. Something to do with cold heavy air laying on the surface

prevents the warm air from subsiding past the compression point or some

such nonsense. At the time, around mid-night, the theory sounded fine. I

was going to find this layer and VFR it across the ice-cap. I had done

this many times in the Rockies so why not here? Klaus was not happy, but I

was determined.

![]() We called

back to Iceland to tell them of our decision. Basically they said,

"Fine, once out of our airspace and below MEA you will be in

uncontrolled airspace and on your own, Good Luck!" I ducked down

below the cloud layer to 9000ft and continued on. And on and on and on.

Klaus began to suspect the GPS. According to the forecast winds aloft and

our true airspeed and the indicated airspeed, we were dead on schedule.

But, time seemed to drag and drag. The ocean seemed endless. Only after

forever and a day we finally spotted the Greenland coast. My heart double

beat in excitement. Klaus let out a sigh of relief. We could see the coast

and the mountains clearly in the slightly misty air below the overcast.

We called

back to Iceland to tell them of our decision. Basically they said,

"Fine, once out of our airspace and below MEA you will be in

uncontrolled airspace and on your own, Good Luck!" I ducked down

below the cloud layer to 9000ft and continued on. And on and on and on.

Klaus began to suspect the GPS. According to the forecast winds aloft and

our true airspeed and the indicated airspeed, we were dead on schedule.

But, time seemed to drag and drag. The ocean seemed endless. Only after

forever and a day we finally spotted the Greenland coast. My heart double

beat in excitement. Klaus let out a sigh of relief. We could see the coast

and the mountains clearly in the slightly misty air below the overcast.

At this point Red Ericson's uncle turned

tail.

![]() The relief, however, was short lived as time continued to slow to a crawl.

Again we checked the GPS. Our ground speed, in fact, was starting to

pick-up as we fell into the lee of the huge island. Despite the extra

speed, the island, the coast, and the mountains never got any closer.

After another hour we were in a state of despair. How could we be going so

fast, our ground speed was now approaching 155knts, and not be getting any

closer? Eric the Red's uncle, the first Viking to attempt the sail to

Greenland, went through the same illusion. After many weeks of sailing

without apparent movement, he concluded that a sea monster or devil must

be holding them in place and they finally beat a hasty retreat in fear.

Eric the Red's uncle never became as famous as his nephew and for good

reason. I can't even remember his name.

The relief, however, was short lived as time continued to slow to a crawl.

Again we checked the GPS. Our ground speed, in fact, was starting to

pick-up as we fell into the lee of the huge island. Despite the extra

speed, the island, the coast, and the mountains never got any closer.

After another hour we were in a state of despair. How could we be going so

fast, our ground speed was now approaching 155knts, and not be getting any

closer? Eric the Red's uncle, the first Viking to attempt the sail to

Greenland, went through the same illusion. After many weeks of sailing

without apparent movement, he concluded that a sea monster or devil must

be holding them in place and they finally beat a hasty retreat in fear.

Eric the Red's uncle never became as famous as his nephew and for good

reason. I can't even remember his name.

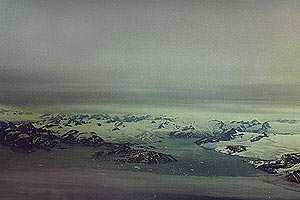

![]() Klaus and

I eventually figured out that we were suffering from "Severe

Clear." A condition where clear, usually cold, air magnifies the

distant objects. The greater the distance (or altitude) the greater the

magnification. The closer you get the less the magnification. The

illusion, on the horizontal, is that you are not getting any closer. When

we finally reached the mouth of the inlet we planned to follow inland we

also realized the magnitude of the island and the approaching glacier. It

was enormous beyond our comprehension. The calving icebergs themselves

were the size of small islands. Greenland, we had to remind ourselves,

should have been a continent. Calling it an island does not do it justice.

At this point I began to get worried about my decision to go it below.

Klaus and

I eventually figured out that we were suffering from "Severe

Clear." A condition where clear, usually cold, air magnifies the

distant objects. The greater the distance (or altitude) the greater the

magnification. The closer you get the less the magnification. The

illusion, on the horizontal, is that you are not getting any closer. When

we finally reached the mouth of the inlet we planned to follow inland we

also realized the magnitude of the island and the approaching glacier. It

was enormous beyond our comprehension. The calving icebergs themselves

were the size of small islands. Greenland, we had to remind ourselves,

should have been a continent. Calling it an island does not do it justice.

At this point I began to get worried about my decision to go it below.

With freezing water below and freezing

rain above we try crossing the island

below the cloud layer. It does not look promising.

![]() That decision became critical as we finally approached to where we could

see where the top of the ice-cap should have been. We could not

differentiate between where the cloud ended and the ice-cap began. The two

melted into a misty white fog. The warm front was sweeping the glacier

right to the ground. So much for expert advice. We were about to fly into

a whiteout. Two incidences came to mind. The first was the Air New Zealand

747 that flew into Vinson Massif in the Antarctic during a whiteout. The

pilot simple did not distinguish the hard stuff from the soft stuff. Ice

from cloud. There were no survivors.

That decision became critical as we finally approached to where we could

see where the top of the ice-cap should have been. We could not

differentiate between where the cloud ended and the ice-cap began. The two

melted into a misty white fog. The warm front was sweeping the glacier

right to the ground. So much for expert advice. We were about to fly into

a whiteout. Two incidences came to mind. The first was the Air New Zealand

747 that flew into Vinson Massif in the Antarctic during a whiteout. The

pilot simple did not distinguish the hard stuff from the soft stuff. Ice

from cloud. There were no survivors.

![]() The other

incident was the time the Bandeirante pilot, who was quietly flying in IMC

over Greenland, noticed the aircraft beginning to mysteriously slow down.

He added power, but to no avail as it continued to slow - to a complete

stop! At that point he had to shut down and step out. He had made a

perfect full power belly landing on the top of Greenland. Luckily he was

rescued several days later, slightly embarrassed.

The other

incident was the time the Bandeirante pilot, who was quietly flying in IMC

over Greenland, noticed the aircraft beginning to mysteriously slow down.

He added power, but to no avail as it continued to slow - to a complete

stop! At that point he had to shut down and step out. He had made a

perfect full power belly landing on the top of Greenland. Luckily he was

rescued several days later, slightly embarrassed.

![]() We called

Sondre Stromfjord Greenland on the HF for weather, and we were told our

destination Narsarsuaq was going down slowly, but was still above

minimums. Sondrestrom, our alternate further north, was still in the

clear. I knew that in order to make it we would have to climb above the

cloud and through the icing layer as Klaus had originally wanted to do. If

we were to climb toward the glacier and we were to pick up icing, slowing

or stopping our climb, we could be in big trouble with the mountains

ahead. But, I decided, that if we were to climb eastbound, away from the

glacier and out over the ocean we could always descend again if need be.

In other words, we could test the waters, or ice, without any real danger.

Or so I thought.

We called

Sondre Stromfjord Greenland on the HF for weather, and we were told our

destination Narsarsuaq was going down slowly, but was still above

minimums. Sondrestrom, our alternate further north, was still in the

clear. I knew that in order to make it we would have to climb above the

cloud and through the icing layer as Klaus had originally wanted to do. If

we were to climb toward the glacier and we were to pick up icing, slowing

or stopping our climb, we could be in big trouble with the mountains

ahead. But, I decided, that if we were to climb eastbound, away from the

glacier and out over the ocean we could always descend again if need be.

In other words, we could test the waters, or ice, without any real danger.

Or so I thought.

![]() I turned

east and started our climb. Immediately entering the cloud we began to

pick up clear ice. The accumulation was fast and heavy and within a couple

thousand feet we were so loaded we could no longer climb. Even with full

defrost heat on I had only a tiny hole in the windscreen to see out of. At

13,000ft the clouds did not look any brighter above. With full power we

were going no where but down. I never even had to change altitude. I only

barely pulled the power lever back an inch and the beaver started to

plunge downward, almost out of control. I did not count on losing control.

I turned

east and started our climb. Immediately entering the cloud we began to

pick up clear ice. The accumulation was fast and heavy and within a couple

thousand feet we were so loaded we could no longer climb. Even with full

defrost heat on I had only a tiny hole in the windscreen to see out of. At

13,000ft the clouds did not look any brighter above. With full power we

were going no where but down. I never even had to change altitude. I only

barely pulled the power lever back an inch and the beaver started to

plunge downward, almost out of control. I did not count on losing control.

![]() The

control surfaces were so iced up that they were mostly ineffective. I kept

the airspeed up to prevent a stall and walked the rudders constantly to

keep the beaver's wings level. A wing drop would have been critical in

this condition. I managed to keep her right side up as we plunged down for

what seemed an eternity. Finally, at about 8,000ft we broke out. But, we

did not stop there. I was counting on the warmer air and warm rain to melt

the ice, but we continued down until nearly 4000ft over the ocean before

enough ice melted off that we could regain control and maintain our

altitude.

The

control surfaces were so iced up that they were mostly ineffective. I kept

the airspeed up to prevent a stall and walked the rudders constantly to

keep the beaver's wings level. A wing drop would have been critical in

this condition. I managed to keep her right side up as we plunged down for

what seemed an eternity. Finally, at about 8,000ft we broke out. But, we

did not stop there. I was counting on the warmer air and warm rain to melt

the ice, but we continued down until nearly 4000ft over the ocean before

enough ice melted off that we could regain control and maintain our

altitude.

![]() Klaus,

having just gone through a wild joy ride, was not happy. He kept saying as

we continued to plunge, "We have to get control of ourselves, we have

to get control of ourselves." I must give him credit, as there is

nothing more difficult for a pilot than to be in the right seat and have

to trust someone else. As the ice melted and we started our climb back up

to just below the cloud, Klaus finally regained his composure, but

repeating out loud. "No, I have to get control of myself, I must get

control of myself." At that point, Klaus broke out the oxygen and

took a few minutes of long deep breaths to clear his head. I could not

help but be amused at the irony of his teasing me earlier about my use of

oxygen. I had been on it the whole time above 10,000ft.

Klaus,

having just gone through a wild joy ride, was not happy. He kept saying as

we continued to plunge, "We have to get control of ourselves, we have

to get control of ourselves." I must give him credit, as there is

nothing more difficult for a pilot than to be in the right seat and have

to trust someone else. As the ice melted and we started our climb back up

to just below the cloud, Klaus finally regained his composure, but

repeating out loud. "No, I have to get control of myself, I must get

control of myself." At that point, Klaus broke out the oxygen and

took a few minutes of long deep breaths to clear his head. I could not

help but be amused at the irony of his teasing me earlier about my use of

oxygen. I had been on it the whole time above 10,000ft.

The pure isolation and severity of the

inlets made our blood chill.

![]() Now we had the big decision to make. With the ice on our antenna we had

lost contact with Greenland and the weather updates. Considering the time

and fuel wasted, and the deteriorating condition of the weather at our

destination, I decided to head back to Iceland. As much as I hated the

idea, I figured that we had to admit defeat. I made the decision, in part,

not to scare Klaus any further, but Klaus argued otherwise. "There is

no way in hell that I am going back across that ocean only to run our of

fuel 20 miles short of the airport. No way." He wanted to head to our

alternate further up north. We were positive the weather would still be

holding there. Klaus put in the co-ordinates in the GPS, and my heart sank

as we realized that it was 800 miles further north. If we headed there,

especially after losing the HF contact and without a updated weather

report, we were committing ourselves. From there we would have no

alternative. Our fuel would be too low to go on.

Now we had the big decision to make. With the ice on our antenna we had

lost contact with Greenland and the weather updates. Considering the time

and fuel wasted, and the deteriorating condition of the weather at our

destination, I decided to head back to Iceland. As much as I hated the

idea, I figured that we had to admit defeat. I made the decision, in part,

not to scare Klaus any further, but Klaus argued otherwise. "There is

no way in hell that I am going back across that ocean only to run our of

fuel 20 miles short of the airport. No way." He wanted to head to our

alternate further up north. We were positive the weather would still be

holding there. Klaus put in the co-ordinates in the GPS, and my heart sank

as we realized that it was 800 miles further north. If we headed there,

especially after losing the HF contact and without a updated weather

report, we were committing ourselves. From there we would have no

alternative. Our fuel would be too low to go on.

![]() Suddenly

the image struck me. Our destination was only 100 miles away. If we could

break through the cloud layer we could still try for our original

destination and keep the northern base of Sondrestrom as our alternate as

planned. How? Picture this. A classic warm front moving south to north.

Where we were the cloud base was now down to 8000ft. Tops about 15,000ft.

Icing from 8000ft to about 13,000ft where after that it would be too cold

to further collect. That 5000ft of icing layer is what we tried to break

through and failed. The classic warm front, remember? Remember the drawing

on the IFR portion of your ATPL exam? Of course.

Suddenly

the image struck me. Our destination was only 100 miles away. If we could

break through the cloud layer we could still try for our original

destination and keep the northern base of Sondrestrom as our alternate as

planned. How? Picture this. A classic warm front moving south to north.

Where we were the cloud base was now down to 8000ft. Tops about 15,000ft.

Icing from 8000ft to about 13,000ft where after that it would be too cold

to further collect. That 5000ft of icing layer is what we tried to break

through and failed. The classic warm front, remember? Remember the drawing

on the IFR portion of your ATPL exam? Of course.

![]() All we had

to do was fly about 100 miles northwest and then punch through. And we

did. As we got further north the cloud base above us rose and got colder.

The tops got higher, but at that altitude the moisture was pure ice

crystals. Best of all, the icing layer would only extend from about the

base of 11,000ft to the freezing level of about 13,000ft. The theory

worked perfectly. We began our climb through the cloud and again we began

to pickup ice. But, by the time it started to accumulate, however, it was

too cold to collect any further. Klaus was yelling, "I can see blue

sky, keep her going." We broke out at 16,000ft and leveled out at

16,500ft. Sunshine and blue blue sky. We could see heaven.

All we had

to do was fly about 100 miles northwest and then punch through. And we

did. As we got further north the cloud base above us rose and got colder.

The tops got higher, but at that altitude the moisture was pure ice

crystals. Best of all, the icing layer would only extend from about the

base of 11,000ft to the freezing level of about 13,000ft. The theory

worked perfectly. We began our climb through the cloud and again we began

to pickup ice. But, by the time it started to accumulate, however, it was

too cold to collect any further. Klaus was yelling, "I can see blue

sky, keep her going." We broke out at 16,000ft and leveled out at

16,500ft. Sunshine and blue blue sky. We could see heaven.

![]() Soon the

ice sublimated off in the cold and we were able to reestablish contact

with Sondrestrom. They had been calling, but weren't too worried. The best

news was that our destination weather was still holding out on the

minimum. We could try an approach there. We continued on at 16,500ft --

both on oxygen.

Soon the

ice sublimated off in the cold and we were able to reestablish contact

with Sondrestrom. They had been calling, but weren't too worried. The best

news was that our destination weather was still holding out on the

minimum. We could try an approach there. We continued on at 16,500ft --

both on oxygen.

Ok, the weather was not this good when we

got there.

![]() Our approach wasn't exactly going to be easy either. The airport was at

sea-level, deep inside a fjord, and surrounded by 9,000ft mountains and

glaciers. The approach is to establish a hold over the beacon, at 16,500ft

and circle down in the hold, using the DME to establish the turns, and

break out somewhere before the minimum of 3500ft. That in itself would not

be the problem. The icing would. If we were to collect ice on the way down

and then not break out at the minimum, how would we get back up again?

Back to square one.

Our approach wasn't exactly going to be easy either. The airport was at

sea-level, deep inside a fjord, and surrounded by 9,000ft mountains and

glaciers. The approach is to establish a hold over the beacon, at 16,500ft

and circle down in the hold, using the DME to establish the turns, and

break out somewhere before the minimum of 3500ft. That in itself would not

be the problem. The icing would. If we were to collect ice on the way down

and then not break out at the minimum, how would we get back up again?

Back to square one.

![]() The tower

gave us an actual ceiling, however, of 3500ft. We were allowed to make the

approach. What could go wrong? Just to be sure of the turns I put the

co-ordinates of the DME into the GPS. I did a turn at 16,000ft to get the

feel for it and then started down. Down and down. Again time stood still.

At 500ft a minute it would take 32 minutes to get down. I wanted to get

through the icing layer as fast as possible so I pulled the power and let

her fall. As the ice built up we lost the DME. The fast descent had let

the ice build up on the belly and blocked the DME antenna. Without it we

would be blind as there was no timing on these turns. GPS to the rescue. I

readjusted my scan to the GPS reading, which I had doubled checked earlier

as corresponding, and flew the rest of the approach. At 3800ft we still

could not see the ground. At 3500ft I was getting ready to check my

descent, when Klaus rang out "I've got visual, keep her going, keep

her going, yes! We made it."

The tower

gave us an actual ceiling, however, of 3500ft. We were allowed to make the

approach. What could go wrong? Just to be sure of the turns I put the

co-ordinates of the DME into the GPS. I did a turn at 16,000ft to get the

feel for it and then started down. Down and down. Again time stood still.

At 500ft a minute it would take 32 minutes to get down. I wanted to get

through the icing layer as fast as possible so I pulled the power and let

her fall. As the ice built up we lost the DME. The fast descent had let

the ice build up on the belly and blocked the DME antenna. Without it we

would be blind as there was no timing on these turns. GPS to the rescue. I

readjusted my scan to the GPS reading, which I had doubled checked earlier

as corresponding, and flew the rest of the approach. At 3800ft we still

could not see the ground. At 3500ft I was getting ready to check my

descent, when Klaus rang out "I've got visual, keep her going, keep

her going, yes! We made it."

Safely down on the runway we can look

north east

toward the mountains we crossed to get here.

![]() The best part came when I called visual and asked for a visual that would

take me for a little tour down the valley before landing. The tower asked

for a special request from the Dash-7 taxiing out. Would you allow the

Danish Prime Minister's Dash-7 to taxi out and take-off while you are on

your approach? Otherwise they will have to wait. Klaus and I looked at

each other. You mean that asshole who wouldn't relay us the weather.

Forget it. So we had the pleasure of making that Danish prima-donna wait

it out for little brother.

The best part came when I called visual and asked for a visual that would

take me for a little tour down the valley before landing. The tower asked

for a special request from the Dash-7 taxiing out. Would you allow the

Danish Prime Minister's Dash-7 to taxi out and take-off while you are on

your approach? Otherwise they will have to wait. Klaus and I looked at

each other. You mean that asshole who wouldn't relay us the weather.

Forget it. So we had the pleasure of making that Danish prima-donna wait

it out for little brother.

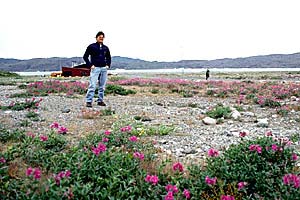

The land is cold. The land is beautiful.

![]() That night in the only hotel in town, Klaus and I treated ourselves to

caribou steaks and red wine. The only other guests in the hotel were the

Danish Prime Minister's party and their Greenland hosts. It was a special

occasion and they had all the tables lined up just across from our single

table. The conversation in Danish was lively and jovial. They were clearly

having a good time. After a particularly animated speech the hosts

presented the Prime Minister (or the PM's wife, I never did figure that

out) with a beautiful full length seal skin coat. She tried it on and

modeled it for all to behold and received an appreciating round of

applause.

That night in the only hotel in town, Klaus and I treated ourselves to

caribou steaks and red wine. The only other guests in the hotel were the

Danish Prime Minister's party and their Greenland hosts. It was a special

occasion and they had all the tables lined up just across from our single

table. The conversation in Danish was lively and jovial. They were clearly

having a good time. After a particularly animated speech the hosts

presented the Prime Minister (or the PM's wife, I never did figure that

out) with a beautiful full length seal skin coat. She tried it on and

modeled it for all to behold and received an appreciating round of

applause.

![]() Ok, it was

our second bottle of red wine, but Klaus could not help himself in making

a comment. To be sure I would hear him over the commotion he said very

loudly, in English, "We would appreciate her modeling the coat a

whole lot more if she wasn't wearing anything underneath!" The room

suddenly became quiet. An awkward silence was followed by a cough and a

snicker. Klaus stared at me in disbelief. He forgot. They could all also

speak perfect English. One of the party chuckled and nodded in agreement,

"Yaah, that would make it more interesting." And everyone broke

out in laughter. The Canadian bush pilots strike again.

Ok, it was

our second bottle of red wine, but Klaus could not help himself in making

a comment. To be sure I would hear him over the commotion he said very

loudly, in English, "We would appreciate her modeling the coat a

whole lot more if she wasn't wearing anything underneath!" The room

suddenly became quiet. An awkward silence was followed by a cough and a

snicker. Klaus stared at me in disbelief. He forgot. They could all also

speak perfect English. One of the party chuckled and nodded in agreement,

"Yaah, that would make it more interesting." And everyone broke

out in laughter. The Canadian bush pilots strike again.

I get dressed up to have dinner with the

Prime Minister.

Story and Images by John S Goulet

![]() Goose Bay Canada Across

to Labrador our entry into Canada

Goose Bay Canada Across

to Labrador our entry into Canada

![]()

The attitude indicator will take you back to the ferry flight introduction page.

Where all our flying is cross country.

Last modified on Aprin 21st, 2013.

© Virtual Horizons, 1996.