|

|

| The secret is to pull her free of the surface tension just below the stall speed and keep her airborne. Thrust rather than pure aerodynamics will be what gets you flying. My favorite trick is to launch off the last big swell and then dump the flaps to leave her "hanging on the prop!" |

The only difference with a

heavy load is that you have to milk or play the controls according to

the incoming swells. As you will be on the water longer than when

lightly loaded, you have to feel out each swell and ride them as clean

as possible to prevent crashing into the big ones. This initially meant

pulling back on the control column to go up rather than through the

largest swells, minimizing drag and maximizing speed, and then pushing

ahead during a periods of smaller swells to gain the air speed for

creating lift. With greater lift the floats will rise in the water

producing less surface drag and increasing the speed needed for

lift-off.

But, once you build up speed then

you will have to push or cut your way through the big swells to minimize

the impact and prevent getting launched prematurely, and then pull the

nose up during the period of smaller swells in an attempt to minimize

surface drag when you are just at or below the stall speed. Like I

mentioned earlier, the secret is to pull her free of the surface tension

just below the stall speed and relax on the control column just enough

to keep her airborne. Thrust rather than pure aerodynamics will be what

gets you flying. My favorite trick is to launch off the last big swell

and then dump the flaps to leave her "hanging on the prop!"

I have tried to analyze good heavy

water pilots as they make these moves to visualize what they do, but to

no avail. Although, I know there is a proper way to take off in heavy

water, there does not appear to be any rhyme or reason that you can

teach in a class room. It is rather “just a feelin” for flying that

you have to learn by doing.

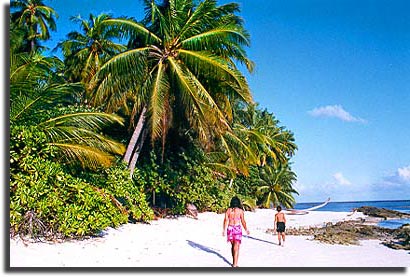

The next two trips I flew and

Ian sat in the right seat as a type of line check. I felt like I had not

flown since my days in Fiji where in fact I had just been flying the

same machine in Africa a few weeks before. The environment was so

different from the muddy brown rivers of the tropical rainforests,

however, I felt out of place for a few legs. Finally after a landing or

two at Holiday Island and a trip to Gangehi, I felt more at ease. It is

easy to look lost flying an aircraft you have several thousand hours in

because of a new and foreign environment.

The last trip of my line

check, I accompanied Ian to the island of Kunfunadhoo. 30 minutes to the

north of Male, Kunfunadhoo is the home to

Soneva Fushi Resort, one of

the most natural and ecological friendly developments in the Maldives.

Sonu and Eva, who are both eccentric and genuine, own the resort. I have

learned over the years that most resort owners are definitely eccentric

and usually self-centered and miserly. Sonu and Eva are certainly

prudent when it come down to business, but they were one of the few owners

who regularly greeted all pilots and staff and guests alike with the

same genuine warmth and aplomb, like you were a long lost cousin from

Madrid.

This philosophy showed in their management style

where ideas or suggestions for improvement could come from anywhere. My

son, who was about seven at the time, decided to attend a management

meeting one morning. He was not only welcomed but was encouraged to make

a presentation about how the island bicycles should have mounted lights

so the guests could easily navigate at night. The next day the GM

ordered a set of bicycle lights and thanked my son for his

contributions. Their managerial style was not top down but radiated from

the center. Sonu and Eva were known for doing things

right and their resort is listed as one of the

World's Top 100 Luxury

Small Hotels.

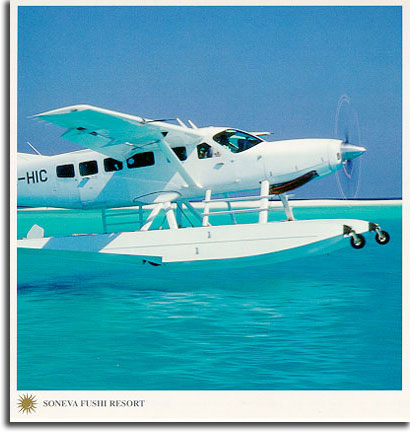

It

was because of them Hummingbird had even one decent aircraft. Sonu was

the younger brother of the new owner of Hummingbird, and he had

requested a factory-fresh leather clad C208 amphib to be their exclusive

guest transport. Sonu got his way and Hummingbird got a new Caravan. In

fact, Sonu was the reason his industrial factory-owning brother, Azad, got into

the airline business in the first place. In order to prop up the

business that he relied upon to transfer his guests to the resort

island, Sonu had bought into Hummingbird Helicopters when they were

being financially drained by the MAT competition. When Sonu was in

threat of being dragged down as well, he called upon his older brother

to carry the day.

It

was because of them Hummingbird had even one decent aircraft. Sonu was

the younger brother of the new owner of Hummingbird, and he had

requested a factory-fresh leather clad C208 amphib to be their exclusive

guest transport. Sonu got his way and Hummingbird got a new Caravan. In

fact, Sonu was the reason his industrial factory-owning brother, Azad, got into

the airline business in the first place. In order to prop up the

business that he relied upon to transfer his guests to the resort

island, Sonu had bought into Hummingbird Helicopters when they were

being financially drained by the MAT competition. When Sonu was in

threat of being dragged down as well, he called upon his older brother

to carry the day.

Azad had the MD for his aluminum

factory in Nigeria look at the feasibility of taking over Hummingbird

and turning it into a competitive floatplane operation. The MD, luckily

for us float plane pilots and unluckily for Azad, knew absolutely

nothing about airlines or airplanes, let alone floatplanes, and came up

with a positive, but badly underestimated assessment. That was the

beginning of a heavy investment of money, aircraft, and experienced

employees into the making of an airline. The dreams of Kit and Sonu become the reality for our

employment.

The factory new 675hp Caravan,

however, was quite nice. Unfortunately the ferry company had done a

wheels up landing at one of the airports enroute and forgot to mention

it on delivery. I noticed on my first walk around that the skids were

missing off the keels and the back keels near the wheels were worn down

to metal mulch. One of the engineers told me that they cut the remainder

of the protective strips off because they were hanging down and broken

on arrival, and didn’t think to mention it to anyone either. Although

that did not stop us from flying, it made me think of a famous Nigerian

saying, "Things fall apart." It literally means that nothing

last forever.

As we approached Soneva Fushi, I could not see any specific area that I would consider a safe landing zone. The island was long and narrow and surrounded by relatively open seas. Although the island was inside the North Baa Atoll, there was really no barrier reef protecting it from the incoming swells. Moreover, the house reef was too tight around the island with no safe landing areas inside. To start operations several weeks before someone had placed a mooring buoy beside the island, but that had proved unusable in any kind of wind as the seas got too rough. So they had moved the buoy inside a nearby lagoon.

The lagoon was large enough to operate out of, but the reef wasn't high

enough to stop the large rolling swells during the high tides. This

lagoon, although absolutely beautiful in color and form, became one of

our most challenging areas to operate into during the monsoons. The

first day Ian and I landed there was uneventful except that a family of

dolphins had decided to play chicken with us as we lined up for final.

They came on to us head on and only dove as the floats touched the

water.

The lagoon was large enough to operate out of, but the reef wasn't high

enough to stop the large rolling swells during the high tides. This

lagoon, although absolutely beautiful in color and form, became one of

our most challenging areas to operate into during the monsoons. The

first day Ian and I landed there was uneventful except that a family of

dolphins had decided to play chicken with us as we lined up for final.

They came on to us head on and only dove as the floats touched the

water.

Ian and I rode in on the dhoni to

the island and were greeted with cold facecloths and cold drinks. We

stayed long enough to enjoy lunch and then loaded our passengers and

headed back to Male. The passengers were government representatives

inspecting the resort after a major generator fire. Even with no power

the guests had not wanted to leave the island, but Soneva Fushi was forced to

shut down because the health department said so.

Some of the guests had to literally

be carried off the island, including Paul McCartney and his family. Ian

had evacuated them in the new Caravan. Over the next two years Soneva

Fushi

definitely became my family's favorite island retreat. My wife casually

remarks that we lived next door to the villa where Linda

McCartney stayed "in the spring of her death."

End of Part Three

Article and Images by John S Goulet

![]()

Note from the Editor. Hummingbird Helicopters became Hummingbird Island Airways, and Hummingbird Island Airways no longer exists. It has been sold out, and reincarnated as Trans Maldivian Airways. This story is about the two years it was HIA.

For maintenance concerns about operating your Caravan in saltwater,

read

Seaplanes & Salt Water

Click Here for Hummingbird Twin Otter Desktop Image.

![]()

Use the attitude indicator as your guide back to Knowledge Based

Stories.

Top of this

page.

Top of this

page.

The

Bush Pilot Company

Last modified on

August 22, 2006 .

© Virtual Horizons, 1996.

He

could have approach from either direction and put the crosswind at 90

degree to our left, but he knew better. Most floatplanes and tail

draggers will weather cock to the left, which makes a left crosswind

difficult anyway, but the additional culprit working your nose to the

left is asymmetric thrust. The Caravan is especially difficult to

control on take-off or landing with a strong left cross wind and most

knowing pilots will avoid it when ever possible. The Caravan will

control better with a right wind and you can use the power leverage to

your advantage. In other words, when you add power for take-off or to

get you out of a disintegrating situation by pushing the nose down, you

want to be able have an effect that will lever you away from the

crosswind.

He

could have approach from either direction and put the crosswind at 90

degree to our left, but he knew better. Most floatplanes and tail

draggers will weather cock to the left, which makes a left crosswind

difficult anyway, but the additional culprit working your nose to the

left is asymmetric thrust. The Caravan is especially difficult to

control on take-off or landing with a strong left cross wind and most

knowing pilots will avoid it when ever possible. The Caravan will

control better with a right wind and you can use the power leverage to

your advantage. In other words, when you add power for take-off or to

get you out of a disintegrating situation by pushing the nose down, you

want to be able have an effect that will lever you away from the

crosswind. The

first day in Ari Beach, however, I switch seats and flew the take-off.

Although I could have duplicated Ian’s crosswind technique as I had

used it frequently getting in and out of Forcados and Bonny Island on

the Atlantic side of Africa, I wanted to show Ian how I would do a rough

water take-off if I could not parallel or if the wind got too strong.

The upper limit of the Caravan is at about 24 knots, and then you have

to face the music. In this case the freshening wind had picked up

considerable since we landed.

The

first day in Ari Beach, however, I switch seats and flew the take-off.

Although I could have duplicated Ian’s crosswind technique as I had

used it frequently getting in and out of Forcados and Bonny Island on

the Atlantic side of Africa, I wanted to show Ian how I would do a rough

water take-off if I could not parallel or if the wind got too strong.

The upper limit of the Caravan is at about 24 knots, and then you have

to face the music. In this case the freshening wind had picked up

considerable since we landed.