The Orinoco Delta:

Proven Ability!

Part Three

![]()

| We sipped the whiskey slowly, listening to the ice cubes gently clinking within the sweating glasses. Then Molano began to weave a magical tale of Pan American during the early glory days of the '20's and '30's when air travel was just beginning in Venezuela. I sat and sipped and listened. I was to learn many wondrous things from this ancient mariner of the sky. |

![]()

![]() The

next day Ali had to head back to Caracas and Komander showed up to start

his operational training. Since there is no better training than on the

job training I decided to continue the contract from the National Guard

and work in the training when and where possible. That way Komander could

get first hand experience at decision making and flying at the same time.

We started off with some prerequisite airwork and some takeoff and

landings. Again we did the touch and goes at the tourist camp of Boca de

Tigre, but this time we took in the invitation to stop for lunch. It was

the first time they had the aircraft stop at their camp. I took the

opportunity to show Komander how to taxi through the seemingly impregnable

water hyacinth that newly plagued their waterways.

The

next day Ali had to head back to Caracas and Komander showed up to start

his operational training. Since there is no better training than on the

job training I decided to continue the contract from the National Guard

and work in the training when and where possible. That way Komander could

get first hand experience at decision making and flying at the same time.

We started off with some prerequisite airwork and some takeoff and

landings. Again we did the touch and goes at the tourist camp of Boca de

Tigre, but this time we took in the invitation to stop for lunch. It was

the first time they had the aircraft stop at their camp. I took the

opportunity to show Komander how to taxi through the seemingly impregnable

water hyacinth that newly plagued their waterways.

Komander told me the water hyacinth was not

native to Venezuela and was imported from West Africa by some ignorant

expatriate who brought the plant into the country to brighten up their

water garden. When the plant escaped it quickly took over the fresh water

habitations, as there was no natural protection to control it’s spread.

Komander was quite indignant about this terrible African invader that

unnaturally choked their waterways. The funny part was that the West

Africans had told me exactly the same story to explain the devastating

spread of water hyacinth into their native rivers during the late 1980’s,

except in reverse. They blamed the English expatriates for bringing water

hyacinth from South America to liven up their water gardens.

As we taxied through the thick vegetation

the propeller chopped and threw green leaves skyward like tossed salad.

The prop turned green, but the soft leaves did no harm as we slowly made

our way through toward the resort. If the hyacinth bunched up too tightly

in front of the floats we would reverse slightly to get the vegetation

raft off center and then continue. The only problem we had to watch for

was the ICT: inter-cowling temperatures. With too much beta and reverse

and not enough cooling air coming through the cowling the oil temperatures

would start to rise and then the oil pressure would drop. At that point we

would have to let the aircraft run into wind for a short period to let the

temperatures cool.

Once we had found a clear section of water

I had Komander drop the anchor and the resort boat came to pick us up. We

left the floatplane in the channel as we could see it from the shore. If

it pulled anchor we would have lots to time to reach it before it got

away.

At the resort we were treated as special guests with a meal and a tour of the premises. The most memorable meeting was between Captain George and the pet baby tiger. Actually it was a full-grown Ocelot that was kept on a leash to keep it from making good it’s escape. It was friendly enough and seemed to like Komander. They made a good pair. Partly civilized, partly bush.

Komander was experiencing the same problems that plagued Ali. They both

could fly, but they were not able to loosen up and handle the aircraft

when it needed handling. The Caravan can be a handful and under certain

flight conditions the pilot really has to manhandle the aircraft like a

stubborn bronco. Komander’s 727 training made him too civilized to

really be seen working the controls. He tried to set up and let the

aircraft do all the work. That was fine for long finals into runways and

big rivers, but would not work for getting the Caravan in and out of the

rainforest rivers of the Orinoco Delta. Many of the locations the National

Guard wanted us to land at were in narrow winding rivers that were lined

by 100-250 foot trees. Getting in and out meant making 30-45 degree banked

turns onto short final, and touching down on one float with no “way out”

options.

That was easy for an experienced floatplane

pilot, but how do I teach that to a 727/Hughes 500 pilot? As we tried

again and again to get into a tight river location deep in the rainforest,

it suddenly dawned on me that Komander was uncomfortable with the

proximity of the trees. It was not natural for a fixed wing pilot to be

nearly brushing the leaves 200 feet in the air with his wing tips. So I

asked him, “How would you do this approach with the helicopter?” He

did not hesitate to answer with his hands showing me how he would make a

steep approach over the tall trees, sweep the curve of the river in a

tight arc, and flare just as he reached the short straight stretch beyond

the corner.

I said, “Ok, pretend you are flying the

Huey at 85 knots and that you are making the same approach and that

instead of transiting to a flare, you will flare at 55 kias to touch down

on the water. Think of the floatplane as a helicopter and fly it around

that sweep of trees.”

Watching Komander make that transition from

a 727 pilot to a bush pilot was a good feeling for me as an instructor. I

knew that I had found his resonance cord and struck it. Komander flew that

Caravan around the bend and touched it down on the glassy tea colored

waters of Guacapara Cano like he had been landing there all his life. He

was thrilled with himself as well, not because he doubted his piloting

skills, but because he realized that floatplane flying could provide the

same kind of proximity thrills that helicopter flying could. Komander, if

nothing else, was going to enjoy his life style as a bush pilot.

Our next mission was to fly back to the

Orinoco to check out a National Guard location that I had previously

missed with Ali. We headed up to the mouth of the Amacuro River and

scouted out the guard post. It looked manned, but we decided to land and

find out for sure. Komander landed into the mouth of the river right past

a collection of rough looking buildings and a half sunken boat. We turned

around and slow taxied back to the building only to be met by a platoon

under siege. Or at least the guards posted there thought so.

The building windows and doors were filled

with half hidden marines brandishing automatic weapons aimed directly at

us. The National Guards failed to mention that this was a Navy base and

not a National Guard base. Komander and I shut down, not daring to attempt

to flee and drifted with hands in the air to let them know we were not

armed. I can’t imagine what they thought we were doing dropping in from

above smack dap into their bored and unimaginative lives. After the

hysteria of the moment calmed, several of the marines managed to get an

old rubber dinghy fired up and came out to meet us.

Komander showed them our letter from the

National Guard and explained in Spanish how we were supposed to prove our

landing ability so that the NG could better support the Navy in their

times of need. I guess that satisfied them. The guns came down and after a

one sided exchange of cigarettes they allowed us to go.

Unfortunately that was not to be the end of

our authority troubles. The next day Komander and I were checking out the

area of Punta Marius where the villagers lived in stilt houses perched in

the fast waters of the tidal delta flats. We did a couple of landings and

talked to the villagers who came out hastily dressed in their finest beads

and silver to find out what this strange contraption was doing in their

river. They were obviously extremely poor and thought we had something to

do with the oil work that was going on further west. The men were looking

for work.

We left there and headed west toward the

center of the newest oil development. Pedernales is the oil Mecca of the

Occidental region run by BP. There was a tank farm, a camp, and a runway,

as well as a little city of villagers trying to make a living off the

redistribution of the oil worker’s relative wealth. If I had not know

better I would have thought I was in Escravos Nigeria in the Niger River

Delta. The similarities were striking.

In fact, just off Pedernales in the river

right beside the island of Misteriosa (Mysterious) was the Santa Fe swamp

drill rig the Key Victoria. It is hard to describe my excitement

when I spotted an old friend that I had flown to many times in the swamps

of Nigeria. Flying over the Key Victoria was like returning home

after being away for many years. I had Komander fly a steep orbit over the

rig several times so I could take some pictures. Since Misteriosa Island

was on our National Guard itinerary I decided to have Komander land in the

large river mouth and do some practice taxiing around the flotilla of

barges and tugs that accompanied the giant drill rig. After all if they

were going to fly for the oil industry then the pilots better get used to

maneuvering within the marine environment.

Komander radioed his intentions on the

Pedernales mandatory frequency and we set up for landing. We knew that

there was some notam against any landings or takeoffs within 3 kilometers

of the working rig, but I knew how to circumvent such notams written for

helicopters. I placed the rig position in the GPS and then had Komander

land just outside the 3 km zone. Then we made like a boat and step taxied

the rest of the way into the working area. Just to make sure there were no

further restrictions (we were still nervous from the Navy encounter) we

stayed off about a kilometer, and played around the tugs and barges. I

showed Komander how to taxi and tie up against the back of a tug and how

to avoid getting trapped by the tidal flow against an anchored barge and

other valuable insights on how to work a floatplane in the industrial

world of oil service.

Then for the take-off we step taxied

outside the no flying zone and lifted off. Komander again radioed our

intentions and I felt like we had accomplished something positive toward

proving that the floatplane had just as much a future in the development

of the Venezuelan oil industry as it did during the heyday of the Nigerian

oil industry. Just then a Spanish speaking voice of authority came in over

the radio calling 733C. I watched poor Komander go from a position

of authority to a position of quiet resignation as he was obviously

getting berated in Spanish from the voice on the other end. I tried to get

Komander to explain to me what was going on, but he could hardly talk. Not

to mention that he almost stopped flying. The “aviate” and “navigate”

had given way to pure “communicate.”

I knew that if I could get into the

conversation, that whatever we were accused of doing, I could talk our way

out of. I was good at that from having flown in Africa for many years. I

took over the controls and let Komander have some thinking room, and then

began to coach him on how to talk our way out of our predicament. Of

course, we were accused of landing within the restricted zone. Deny and

quote GPS coordinates. We were accused of flying in the same zone without

authorization. Apologize and quote the National Guard authority to scout

out and land at Misteriosa Island. We were accused of not announcing our

intentions. Deny and tell them to check their tapes for our unanswered

calls. (I knew they would have no tapes.)

Finally in exasperation the voice declared

that he was not only the National Guard representative for the area but he

was also the aviation representative for BP, and he was not to be trifled

with. Agree and remind him that it is bad airmanship to argue on the

radio. Luckily his professionalism prevailed and he said he would be in

contact. The voice, of course, was none other than Señor himself, the

Aviation Manager of BP.

Komander was convinced that his flying

career was over. I was convinced that we were out of the woods. Only a

conversation with Señor would define the situation either way. Suddenly

Komander was not so sure he wanted to be a bush pilot. He could see his

many years of experience and many dollars of training going down the river

with a violation and suspension of his licence. I could only see another

territorial bluff from an authoritarian figure. Komander was not used to

bucking the system. I knew no other way.

On returning to Maturin we retreated to our

hotel room. I did not know how we were going to hear from him, but I knew

it was coming. While I was in the shower Komander phoned me, his voice

audibly shaky, and said the LTA base manager, who answers directly to the

GM, has flown out from Caracas to deal with this crisis. He needed to come

see me immediately as the manager was very upset about this whole

incident. I was just out of the shower, but I thought he would be a few

minutes. So I said, “yeah, come on up.”

When Komander knocked just seconds later, I

was still wrapped in my towel and dripping wet when I opened the door.

Much to their embarrassment, the manager was standing right in the

doorway, and the manager turned out to be a beautiful young woman. She

giggled, turned red and apologized in Spanish all in one quick motion. I

just tightened my towel and invited them in. I knew I had disarmed her.

Whatever rank she was going to try to pull on me went out with her giggle.

If she was to be my boss, she would have to work with me on this.

I further disarmed her by quickly taking

the blame for the incursion earlier in the day and tried to distance

Komander from any blame or repercussions. I also explained to her that LTA

need not worry and they did not need to lose their main oil service

contract on account of some territorial argument between a helicopter

pilot and a floatplane pilot. I told her I was confident that I would only

have to talk to el Señor and the matter would be settled. She was not

reassured and told me that the GM himself had heard about the incident and

was very upset. She warned that she was going to have to ground us.

I used her cell phone and phoned the GM

directly. I told him what I told her, and added that this was no reason to

discontinue the training. In fact, I would visit the Señor myself to talk

this crisis through. Although the GM sounded truly worried I must give him

credit. He agreed and told me to continue. He trusted me and wanted to

forge ahead. The young manageress, Cynthia, could not believe how I had

talked myself out of that one. She even had to talk to the GM herself to

verify before letting us go. To finalize my control of the situation I

then asked her out to dinner. She agreed… but only if I got dressed.

The next day Komander was too upset to fly

so I took the opportunity to visit the 86-year-old Pan Am pilot who the

Aviation Manager of BP had claimed was his mentor. I wanted to not only

meet him, but I wanted to pick his brain about his friend Señor. Our

Caravan engineer, a young man struggling to make his way in the

unforgiving world of Venezuelan aviation, agreed to help me find the old

man and drive me to where he worked.

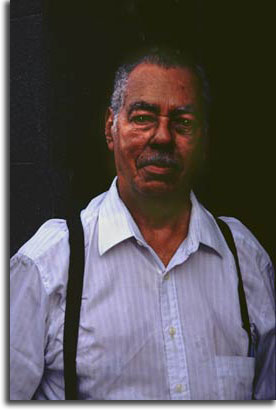

We found him all right. At 86 he owned a brake shop in Maturin, which,

after he retired from flying, he had run for the past 26 years. When we

found him he was just closing shop for the day. It was a beautiful Maturin

evening. The hot daytime air was cooling as the sun’s harsh light warmed

to a golden glow. Amidst the smell of brake fluid, burnt asbestos linings,

and spilt grease baked black in the sun the old pilot was happy to make my

acquaintance, and much to my delight he spoke perfect English.

We found him all right. At 86 he owned a brake shop in Maturin, which,

after he retired from flying, he had run for the past 26 years. When we

found him he was just closing shop for the day. It was a beautiful Maturin

evening. The hot daytime air was cooling as the sun’s harsh light warmed

to a golden glow. Amidst the smell of brake fluid, burnt asbestos linings,

and spilt grease baked black in the sun the old pilot was happy to make my

acquaintance, and much to my delight he spoke perfect English.

He invited me in for a day end drink and I

accepted. He said he kept a bottle in his desk drawer “in case his

girlfriend stopped in.” He pulled out a bottle of Irish crème whiskey,

which he poured into tumblers. We sipped the whiskey slowly listening to

the ice cubes gently clinking within the sweating glasses. Then Molano

began to weave a magical tale of Pan American during the early glory days

of the '20's and '30's when air travel was just beginning in Venezuela and

elsewhere in the world I might add. I sat and sipped and listened. I was

to learn many wondrous things from this ancient mariner of the sky.

One fact that surprised me was that Pan Am

strictly controlled the water landings on their floatplanes and flying

boats. In fact, they only had 2 water landing areas in Venezuela. Hearing

that meant that many of our water locations for the National Guard were

most likely “firsts.” I love being first. Being the first to land at

remote locations was my only chance in life to be an explorer, a pioneer,

and an adventurer. I was doing something no one else had done before.

When I told him about the trouble I had

gotten myself into with his friend Señor, Molano just laughed and poured

us another drink. He asked me if I had learned any Spanish during my

visit. I was embarrassed to say I had only learned un poco, “a little.”

He said if I was to learn any Spanish there was two things to learn first.

One was a phrase to charm the local girls. The other was a phrase I could

use to get out of any trouble with authorities, especially with the BP

Aviation Manager.

Molano’s advice was to simply respond

with “Si Señor,” and nod my head in agreement and repentance. The

next day when I had my meeting with Señor he was so impressed with my

contrition he offered LTA the full support of BP to set up what ever

landing areas we needed to get started in the Delta. He said, "Just

let me know how we can help and we will."

Of course, I also had mentioned how I had

visited and learned to admire his 86-year-old mentor from the lost era of

Pan Am. We both lamented that indeed Pan Am was a sad loss, and agreed

that Molano was a proud reminder of what that era held dear. Honesty, hard

work and integrity. Molano epitomized it all.

|

Molano on Jimmy Angel. “I knew Jimmy alright.” “Jimmy had a

450hp Fairchild.” “Now that airplane had power.” “And Jimmy fixed it himself.” Molano on Pan American: "More than an airline, Pan Am was a school. They trained everyone and did it very well." Molano on his education: "In the land of the blind one eye is king." |

While Komander was still licking his

wounds, I decided to take a flight of my own. I was safe as long as I had

a Spanish speaking co-pilot, which Gamboa was happy to provide. I had been

watching the Delta for the movement of the shock troops of the oil

industry. These were the seismic crews that did the basic search for

possible drill sites. The entire Delta had been shot many years before

when the government assessed that the Orinoco Delta held an enormous

potential for oil reserves. The original seismic, however, had been shot

in 2D and now the oil companies had the power of 3D seismic and PC

computers to do the calculations. The difference was like Cinderella being

able to look into a silver hydride coated mirror compared to the polished

bottom of a copper pot. And what the engineers saw was a thing of beauty.

Huge oil reserves.

The seismic crew, however, was only just

cutting into the edge of the Orinoco Delta. I knew if the Caravan was to

be successful here it had to be able to go where the seismic crews, and

ultimately the oil companies, go. I had seen their work location only

about a 20-minute flight from Maturin where the rivers were young, narrow

and winding, From here the rivers were just beginning to trace their

journey from the swamps through the rainforest and down to the ocean. If I

could get into here I could get into anywhere.

I flew to an area called Guasina,

ironically up the Pedernales, the same river where we had gotten ourselves

into trouble at the mouth. Here the land was higher with majestic dry land

rainforest and huge trees. And where the waters prevailed the swamp was

covered with grass that could grow 3 meters high. The area was highly

sensitive to invasion and was alive with ocelots, jaguar, boa

constrictors, and a variety of other snakes and reptiles. Not to mention

the birds: including eagles, herons, cranes, kingfishers, and toucans that

depended on the area for habitation.

I had Gamboa announce our intentions on the

MF of the area, and we immediately got resistance. One of the helicopter

pilots came on to tell us “this was a restricted area for helicopters

only and that we were not allowed to over fly at low level” I knew this

was pure bullshit and I had Gamboa tell the pilot that this was a VFR

environment where "see and be seen" is the rule, and secondly,

"announce your intentions" because that was what radios were

for. We would announce our intentions and they could pass on their

traffic, thus avoiding any conflicts. Despite his initial reluctance,

especially after what had happened to Komander, Gamboa passed on my

message and eventually the helicopter pilot capitulated.

I found two separate camps along the river.

Apparently they belonged to competing seismic companies each having

different but adjoining blocks. I decided to land at the more difficult

one the furthest up the river. The landing and takeoff area was just long

enough, but the river appeared very shallow. I had no way of knowing by

looking into the tannic colored black waters. So I decided, for the first

run at least, to land down the river in known deep water and then taxi up

the river with the sonar turned on. The water was completely glassy and I

made a short approach and steep turn to final. I was showing off as one of

the helicopter pilots had come to watch our landing.

I made a smooth touchdown and pulled beta

to come to an immediate stop. When you are not sure of the waters you don’t

keep your speed up any longer than necessary. The helicopter pilot came on

the radio to say, in Spanish, “well done.”

The sonar initially showed about 30 feet

but that changed as we taxied up river. As we got near the camp the depth

dropped to 12 feet and then 6 feet. I continued up the river past the camp

and continued to taxi until I felt the banks would be too close to risk a

landing. Here the water was about 3 feet deep but even that was enough for

landings and takeoffs. The river would fluctuate with the rainy season,

but because this was the low water time of year the river could only get

deeper. In other words, where the river was wide enough it was certainly

deep enough.

Getting into the camp was going to be

difficult. There was a small opening where the workers transited to the

shore and they had placed two logs lashed together out from the shore. I

approached the logs in feather and then shut down to ghost in the last

little way like I was in the Otter. The wings both went into the foliage,

but that acted to hold the aircraft in place. In the middle of the river

the current was a couple of knots, but along the banks there was no

current and the aircraft held fast. While I went into the camp, however,

Gamboa volunteered to paddle the Caravan into the middle of the river and

anchor. He was uncomfortable with the branches possibly scratching the

paint on the wings so I let him paddle out, knowing that this would be a

good experience for him.

I walked into the busy seismic camp where

the workers paid no attention to me. With their small camp generator

running they had apparently not even heard the aircraft approach. The camp

manager, a small red-faced Scotsman, was surprised to see me. He

introduced himself but was obviously cautious when I started asking

knowledgeable questions. The seismic crews were under siege from the

environmental groups and were understandably on their guard. He was

noticeably relieved when I explained my intentions and we were both

excited to hear that we had worked Nigeria during the same period. In

fact, he had seen a floatplane come into their camp in the Niger River

Delta on several occasions. I explained that since I was the only

floatplane pilot in Africa during that time frame it must have been me.

Small world.

The Scot then took me on a tour of

their small island in a sea of swamp. He said that to prevent any

permanent environment damage they were using airboats, like the ones in

Florida everglades, to do their work and to transport people and supplies.

They were also using the helicopters, mostly Hughes 500s, to long line

sling loads to the work crew. I did not argue with him, but I could see

from the air that the airboats were wrecking havoc with the swamps and the

sea of grass.

Having used airboats for many years myself

in the wild rice lakes of Canada, I knew what the problems were. For one,

when they established a track to prevent the airboats from wandering, the

track would get beaten and damaged from the continuous traffic to the

point it would not recover easily. That was a necessary evil for

protecting the rest of the swamp.

The second problem was that either because

the grass was too high to see over, or because of the wander lust of the

crew, the airboats were wandering off the tracks anyway and causing much

more damage than what was the intention of the seismic companies. The

meandering trails were evident from the air… where from the water level

it was only possible to see the trail that you were on. How much damage

was anybody’s guess, but I could only imagine the Florida Everglades had

gone through a similar problem with their airboats before regulation.

The big difference the Scot found between

working in Nigeria and Venezuela was the number of people versus the

number of wildlife. In Nigeria there were literally hundreds of thousands

of residents in the Niger River Delta and very few animals. Nigeria had

suffered through a major civil war where a million people starved to

death. The ones that survived did so by eating whatever moved, including

crocodiles, hippos, elephants, and snakes. The human population had

recovered quickly, but the wildlife population never did.

In the Orinoco there were only 25,000

inhabitants in an area roughly the same size as in Nigeria, and according

to the Scot there was an enormous amount of wildlife. When they first set

up camp they started a map to mark where they spotted wild pigs, caiman,

jaguar, ocelots, and boa constrictors and soon the map was full. They

spotted so many animals they finally gave up on the map and concentrated

on keeping from getting bitten. The Scot reckoned that when he was in the

swamp he saw snakes every single day, all of them venomous.

After watching the helicopters come and go

with their sling loads, I headed back to the river to find Gamboa and the

Caravan. He had managed to get the aircraft anchored in the middle of the

river, and now he had to bring it back. With no wind and little current he

managed to get it close enough to shore for me to jump on board, but no

sooner than I had boarded I heard a loud “whoop” and a splash. Gamboa

had gone in, wallet and all. I pushed the Caravan into the middle of the

river and started up making Gamboa stand outside in the warm breeze until

he was reasonably drip-dry. Welcome to the world of floatplane drivers.

The next day Komander was back in

full form and we spent the day visiting several seismic sites. Along the

inner boundary of the delta the seismic crew were living in tents, using

airboats to get around, and the helicopters landed on cleared areas of

high ground in the swamp. Further out toward the ocean, the central and

outer delta, the seismic crew lived in house boats, traveled by speed

boats, and the helicopters landed on make-shift wooden structures built on

pylons along the rivers lined with red mangrove and huge cotton trees. The

temporary helipads placed along the riverbanks were tenuous at best with

the helicopters having to land facing inward toward the trees and having

to takeoff backwards away from the trees. I could not see where BP thought

this was safer than floatplanes, but then the seismic companies could

charter whomever they wanted. They were not bound by the BP regulations.

Komander and I landed at the main camp on

the Cano Pedernales, another branch along the main river that flowed past

the BP oil terminal of Pedernales. I actually took a little longer than

usual to find this camp because it was not where anyone had pointed out on

the map. I had Komander shut down as a workboat approached and we stopped

to talk to the camp manager for a while. He was impressed with our Caravan

and gave me the name of his boss in Maturin.

From here I took Komander back to the inner

delta seismic camps and we landed in a similar river as I had done the day

before and anchored in front of the tented seismic camp. The crew came out

to meet us in a rowboat and took us to shore and invited us to stay for a

camp lunch. We ate a simple meal of fried beef and spicy fried rice and

then went for a short jungle walk. The trees were alive with parrots and

toucans and we saw shadows of monkeys leaping from tree to tree ahead of

us. Here the rainforest was quiet and beautiful and dynamically alive at

the same time. There was no comparison to the deathly quiet of the

Nigerian rainforest where the trees had been stripped of any wildlife.

When I first started working in Nigeria, the flocks of African Grey

Parrots filled the evenings sky. Now they were reduced to a few mating

pairs speedily darting across the open rivers.

I took a picture of a baby toucan and of

the amphib Caravan sitting quietly in the calm river, and then left for

Maturin. I knew that when we were gone from that tranquil river there

would be no trace of us having been there. The floatplane leaves no

footprint.

I do believe in the ecological benefits of

using the amphib Caravan, however, and so in-between flights I managed to

visit some of the managers of the oil service sector where I hoped to

garner some business. Companies like Willbros, Schlumberger, Halliburton,

Smith Tools, and LL&E were all keen to at least give the Caravan a

try. I knew that if they indeed had business in the delta I would be able

to win them over to using an amphib service. My timing was bad, however,

as I only had a few days left before I had to head up to a contract I had

arranged in Churchill Manitoba. None of the managers could rearrange their

schedules in such a short notice so I decided to give another idea I had a

go. I arranged for Komander and myself to fly up to the Canaima National

Park and to stop on Lake Guida along the way.

Canaima is a series of falls on the Hacha

River just north of the savannah area they call La Gran Sabana. I

also had hoped to catch a sight of the tallest waterfalls in the world,

Angel Falls, although it was not actually on the itinerary. The idea of

this trip, however, was to find ideal locations to set house boats along

Lake Guida to fly in sport fisherman like we do in Canada. The lake was

teeming with a fighting variety of huge Peacock Bass which the American

oil servicemen talked about obsessively. It was a perfect job for an

amphib Caravan. I would fly the oil industry people from Maturin or

American tourists from Caracas out to the houseboats where they could

spend 2-3 days fishing on the edge of the wondrous Canaima escarpment. The

flying time was just over an hour compared to taking the entire day to get

there by other means. If you left at 9am they could be fishing by 10:30am.

Normally if they left at 5am one day they would be fishing by 9am the next

day. I was actually amazed that no one had already exploited this

veritable goldmine of a sport fishing market.

We arrived to find a large beautiful lake

held back by a man made power dam. The lake was calm and perfect for

floatplane work but we elected not to land near the dam and to explore

further up the lake toward Canaima. We only found out later that there was

a no fly zone in and around the dam that we had already violated with our

low flying. Not landing was a good decision. On the other end of the

massive lake we did however scout out two other perfect locations for

setting up the houseboats. At the time I was quite excited about this

business prospect as the fishing potential was incredible. I had seen

pictures of the bass that the American Halliburton manager, Joe, had

caught on one of his expeditions. They were beautiful to look at, good to

eat, and moreover, he said, they fought like hell. These Peacock Bass were

an American fisherman’s dream. And the Caravan was the perfect access

tool.

After scouting out the lake we flew directly up to Canaima where the local airline had set up a tourist lodge in this awesome setting of emerald forests, white sand beaches, and plunging water falls. I elected to land on the ugly gravel runway because well… it was there. The flight up was memorable as the landscape reminded me of a backdrop for a movie titled, “The Land Where Time Stood Still.” It was so sculptured and perfect: the high rising escarpments with their varied colored vertical walls, the lush green rolling forested hills, and the cascade of plunging rapids all contributed to a surreal feeling of disbelief. In fact, the area and the falls were featured in two movies that I knew of: “Acrophobia” with John Goodman and “Jungle 2” with Tim Allen. The Canaima Falls scenes were at the beginning of both films. (I told you that so you don’t have to watch the entire movie.)

After a boat trip up to the falls that engulfed us with spray we ate lunch and then had to make the tough decision of passing up the further flight to Angel Falls. It was almost too good to pass up, but I could not really justify it to the LTA manager. The scouting trip for the bass fishing was worthwhile, but a boondoggle to the falls would be a bit out of our way.

With the National Guard contract and the

pilot training completed it was time for me to head back to Canada. Ali,

Komander, and several of our escorts took me out to a local disco for my

last night in Maturin to celebrate. Maturin is known to be the Wild West

of the Occidental oil boom and where there is new money there is soon

trouble to follow. We never had any trouble, but the tight security made

me wonder what had happened to bring all this on. For example, as we got

out of the car the Kevlar vest wearing security guards, armed with

automatic weapons and low slung sawed off shotguns, escorted us inside the

disco with their backs to us facing any potential threats that might come

our way. Then we were frisked for weapons and had to walk through a metal

detector. All this for a drink and a dance!

Unfortunately all my work and scouting came

to no worthwhile end. The oil boom never materialized in Venezuela as the

government led the country into near bankruptcy. Many of the oil service

companies pulled out and LTA eventually sold their amphib Caravan. It was

a sad turn of events because I had proven beyond any doubt the ability to

run a profitable Caravan amphib operation.

I had shown that a Caravan could easily and

safely service the oil industry in the development of the Orinoco Delta.

More importantly I showed that there was potential for developing the

tourist industry along side the bread and butter contracts of the oil

work. There is no reason that some adventurous company could not emulate

the success of the Chevron Caravan in Nigeria and take up where LTA left

off. After all the amphib Caravan has the proven ability to do what it

takes in the Orinoco Delta to be successful.

Article and Images by John S Goulet

![]()

Note from the Editor. LTA moved on and I did as well. I was offered a chance to be on the ground floor of starting a new seaplane company in the Maldives and it was a tough decision not to go back to Venezuela. I made some great friends and really fell in love with the country. It is so large and diverse I would recommend many of its tourist areas, especially the lowland rainforests of the Orinoco Delta, the La Grand Sabana areas of Canaima Falls and Angel Falls, and the Caribbean islands of Los Roque. Each destination is totally different and yet it is feasible to visit all three in a 2-week holiday. Linea Turistica Aereotuy is still in the tourist business and they can still fly you to any or all of these locations with their Grand Caravans.

![]() Click Here to read "Plundering the

Rainforest." A short article by PropThrust on some of the causes of oil related

ecological destruction in the rainforest.

Click Here to read "Plundering the

Rainforest." A short article by PropThrust on some of the causes of oil related

ecological destruction in the rainforest.

![]() Click

Here to read "Wish You Were Here." The story of the Editor's

trip to the beautiful Caribbean Islands of Los Roque.

Click

Here to read "Wish You Were Here." The story of the Editor's

trip to the beautiful Caribbean Islands of Los Roque.

![]()

The attitude indicator will guide you back to Knowledge Based Stories.

Article and Images by John S

Goulet

Top of this page.

Top of this page.

Think Venezuela - the Tourism Directory

Last modified on

April 26, 2007 .

© Virtual Horizons, 1996.