The

Eleventh Hour: Adventures Around

The Arctic Circle

![]()

August, 1966. High inside the Arctic Circle.

![]() Out into the Foxe Basin waters, we taxied

the huge majestic Canso flying boat. We were leaving Igloolic, a fragile looking

settlement perched tenuously, like a tern's egg on a rock, on an island between the giant

Baffin Island and the mainland Melville Peninsular. I would most likely never be back. I

waved goodbye to the native Eskimo onlookers watching from the pebbled beach. None could

see me, propped up by several flotation cushions, sitting in the co-pilot's seat. They

were waving goodbye to their children. As we taxied out, the red roof of the Hudson Bay

Company store grew smaller as the moment drew nearer.

Out into the Foxe Basin waters, we taxied

the huge majestic Canso flying boat. We were leaving Igloolic, a fragile looking

settlement perched tenuously, like a tern's egg on a rock, on an island between the giant

Baffin Island and the mainland Melville Peninsular. I would most likely never be back. I

waved goodbye to the native Eskimo onlookers watching from the pebbled beach. None could

see me, propped up by several flotation cushions, sitting in the co-pilot's seat. They

were waving goodbye to their children. As we taxied out, the red roof of the Hudson Bay

Company store grew smaller as the moment drew nearer.

![]() My father, the Captain, read off the checklist

for take-off. I followed suit and did what I could within my limited reach. After all, I

was only eleven years old. The co-pilot, Chuck Waters, stood behind us mildly amused. I

remember him as being kind and easy going. He must have been trusting as well, because he

was about to standby as an eleven year old boy took the controls of a 34,000lb aircraft,

powered by two Pratt & Whitney 1830 radial engines firing up 1,200 horse-power each.

My father, the Captain, read off the checklist

for take-off. I followed suit and did what I could within my limited reach. After all, I

was only eleven years old. The co-pilot, Chuck Waters, stood behind us mildly amused. I

remember him as being kind and easy going. He must have been trusting as well, because he

was about to standby as an eleven year old boy took the controls of a 34,000lb aircraft,

powered by two Pratt & Whitney 1830 radial engines firing up 1,200 horse-power each.

![]()

I

turned

the big Canso, or Catalina as the Americans called it, into the wind by sliding

down to use both feet on the left rudder. The sky was clear and blue, the wind was cold

and brisk, the water icy green. Small brilliant white ice floes lined the shores and

dotted the horizon. The waves were being blown higher by the freshening north-east breeze,

with distinct white caps pushed over the tops of the mounting waves. A low but powerful

swell ran parallel to the waves. In other words, we were bucking the works.

I

turned

the big Canso, or Catalina as the Americans called it, into the wind by sliding

down to use both feet on the left rudder. The sky was clear and blue, the wind was cold

and brisk, the water icy green. Small brilliant white ice floes lined the shores and

dotted the horizon. The waves were being blown higher by the freshening north-east breeze,

with distinct white caps pushed over the tops of the mounting waves. A low but powerful

swell ran parallel to the waves. In other words, we were bucking the works.

![]() At taxi speed the Canso pitched with the swell.

At take-off speeds, however, we would be pounding them head on. In my father's early days

on the Canso, a Norwegian flying boat captain had shown him how to take off in the most

incredible ocean swells and wind borne waves. My father wasn't worried, but I was. He had

the uncanny ability to always pick the worst moment to let me try my hand at anything.

There were calmer waters and better days.

At taxi speed the Canso pitched with the swell.

At take-off speeds, however, we would be pounding them head on. In my father's early days

on the Canso, a Norwegian flying boat captain had shown him how to take off in the most

incredible ocean swells and wind borne waves. My father wasn't worried, but I was. He had

the uncanny ability to always pick the worst moment to let me try my hand at anything.

There were calmer waters and better days.

![]() This flight, however, was destined to be my

moment, my eleventh hour. And the entire settlement of Igloolic had turned out to watch.

At least in my mind.

This flight, however, was destined to be my

moment, my eleventh hour. And the entire settlement of Igloolic had turned out to watch.

At least in my mind.

![]() "Are you

ready?" he asked.

"Are you

ready?" he asked.

![]() I nodded yes thinking, "no, not now, not

ever." My stomach churned, my knees grew weak. I ran over and over in my mind and

under my breath the procedures he had drilled me with. Like memorizing the Cub Scout's

oath, I told myself. Just like we had practiced on the 65hp Aeronca floatplane back south.

About two thousand four hundred kilometers south. Back home. Think now! Stick back. Power

on. Right rudder. Wait for nose to stop rising. Relax stick. Push forward. Allow to climb

on step...

I nodded yes thinking, "no, not now, not

ever." My stomach churned, my knees grew weak. I ran over and over in my mind and

under my breath the procedures he had drilled me with. Like memorizing the Cub Scout's

oath, I told myself. Just like we had practiced on the 65hp Aeronca floatplane back south.

About two thousand four hundred kilometers south. Back home. Think now! Stick back. Power

on. Right rudder. Wait for nose to stop rising. Relax stick. Push forward. Allow to climb

on step...

![]() "Ok, go for

it," he gave the command.

"Ok, go for

it," he gave the command.

![]() Even at a stretch my finger tips could hardly

push the overhead throttles. I just touched them and dad pushed them ahead steadily. The

engines roared a deafening roar. The props picked up water as they surged ahead and threw

back a vortex of white spray. Even with the control column back, held with all my might

and a little help from the left seat, the nose plowed through the first of the swells

splashing green water over the windshield. My heart pounded as the hull pounded, and I

felt a crippling weakness of fear creeping through my muscles and bones, as water dripped

down all around us.

Even at a stretch my finger tips could hardly

push the overhead throttles. I just touched them and dad pushed them ahead steadily. The

engines roared a deafening roar. The props picked up water as they surged ahead and threw

back a vortex of white spray. Even with the control column back, held with all my might

and a little help from the left seat, the nose plowed through the first of the swells

splashing green water over the windshield. My heart pounded as the hull pounded, and I

felt a crippling weakness of fear creeping through my muscles and bones, as water dripped

down all around us.

![]() "I can't reach the

rudders!" I yelled to no one, as no one could hear me anyway. Like the

throttles, I could just touch them, but to no real effect. The 2,400 horse-power was

slowly turning us left, until the left seat driver kicked in some much needed help. As the

water stopped breaking across the windshield, I pushed the yoke forward and the big

"Pigboat" started to accelerate. We pounded across the tops of the first few

swells, but with a medium load and a brisk cold breeze, we were soon light on the water.

"I can't reach the

rudders!" I yelled to no one, as no one could hear me anyway. Like the

throttles, I could just touch them, but to no real effect. The 2,400 horse-power was

slowly turning us left, until the left seat driver kicked in some much needed help. As the

water stopped breaking across the windshield, I pushed the yoke forward and the big

"Pigboat" started to accelerate. We pounded across the tops of the first few

swells, but with a medium load and a brisk cold breeze, we were soon light on the water.

![]() My actions took on a dream sequence blurring

where every color was pastel and every event in time happened in slow motion. I pulled the

control column back slightly and we were airborne. My heart flew as I realized we were

free from the surface. I was flying!! My hands trembled and my knees shook, but the thrill

of that heart pounding take-off was something that would last a life time. That arctic

trip was my eleventh hour. That precious irrevocable moment before the eclipse of manhood,

pivotal to the rest of your life.

My actions took on a dream sequence blurring

where every color was pastel and every event in time happened in slow motion. I pulled the

control column back slightly and we were airborne. My heart flew as I realized we were

free from the surface. I was flying!! My hands trembled and my knees shook, but the thrill

of that heart pounding take-off was something that would last a life time. That arctic

trip was my eleventh hour. That precious irrevocable moment before the eclipse of manhood,

pivotal to the rest of your life.

![]()

The thought of Churchill always brings back wonderful

memories for me. I spent my eleventh summer in Churchill and points north. My

father, Lorne Goulet, flew an amphibious Canso flying boat for Transair, out of the

airstrip in Fort Churchill. When he first flew to Churchill in 1960 with a Noorduyn

Norseman on straight floats, he had to land on a small lake near the town. When he went up

as a co-pilot on the amphibian Canso in 1962, he had the luxury of an all weather airstrip

courtesy of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The runway in Fort Churchill, I was told, was

one of those built along the Red Route during World War 11.

The thought of Churchill always brings back wonderful

memories for me. I spent my eleventh summer in Churchill and points north. My

father, Lorne Goulet, flew an amphibious Canso flying boat for Transair, out of the

airstrip in Fort Churchill. When he first flew to Churchill in 1960 with a Noorduyn

Norseman on straight floats, he had to land on a small lake near the town. When he went up

as a co-pilot on the amphibian Canso in 1962, he had the luxury of an all weather airstrip

courtesy of the Royal Canadian Air Force. The runway in Fort Churchill, I was told, was

one of those built along the Red Route during World War 11.

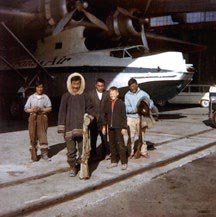

![]() In 1966 my father was a Captain on the Canso

and I accompanied him in early July as we flew north from Winnipeg. I remember myself

mostly from the photographs we took at the time. I was lean and wiry, with hair short

enough to have a brush cut if I had let my father have his way. I wouldn't have it though.

No brushcut for me.

In 1966 my father was a Captain on the Canso

and I accompanied him in early July as we flew north from Winnipeg. I remember myself

mostly from the photographs we took at the time. I was lean and wiry, with hair short

enough to have a brush cut if I had let my father have his way. I wouldn't have it though.

No brushcut for me.

![]() The flight to Churchill was a long arduous

journey for a kid who at the time thought the 90 minute drive from our home town of Lac du

Bonnet to the big city of Winnipeg was endless torture. It didn't help that I was growing

much too fast at the time and that my brain was coursing with the hormones of emerging

manhood. I loved adventure, but I hated traveling. I loved being there, but I hated

getting there. In most bush planes, the deadly combination of droning vibrating engines,

nonstop rocking and bobbing, and the forehead pounding smell of avgas, left me in a

constant state of motion sickness. Flying in the Canso, however, had exceptions.

The flight to Churchill was a long arduous

journey for a kid who at the time thought the 90 minute drive from our home town of Lac du

Bonnet to the big city of Winnipeg was endless torture. It didn't help that I was growing

much too fast at the time and that my brain was coursing with the hormones of emerging

manhood. I loved adventure, but I hated traveling. I loved being there, but I hated

getting there. In most bush planes, the deadly combination of droning vibrating engines,

nonstop rocking and bobbing, and the forehead pounding smell of avgas, left me in a

constant state of motion sickness. Flying in the Canso, however, had exceptions.

![]() The aircraft was so big, compared to the

Norseman and Bellanca Air Bus that I had grown up in, that I could roam around at free

will. If I started getting nauseous, I would simply get up and around to clear my head. My

favorite place was the flight engineer's tower, located in the pylon between the fuselage

and the wings. The flight engineer, Sam, would readily relinquish his station to me to

have an excuse to have a snooze down below. From there I could see the horizons on both

sides and beyond.

The aircraft was so big, compared to the

Norseman and Bellanca Air Bus that I had grown up in, that I could roam around at free

will. If I started getting nauseous, I would simply get up and around to clear my head. My

favorite place was the flight engineer's tower, located in the pylon between the fuselage

and the wings. The flight engineer, Sam, would readily relinquish his station to me to

have an excuse to have a snooze down below. From there I could see the horizons on both

sides and beyond.

![]() The sight of Churchill was always welcome. The

trailer motel we stayed in had a bed to lie on and the food, I remember, was a relief from

the moose meat sausage, black bread, and hard baked pilot's biscuits, that was my father's

standard fare during our long flights in the bush. For an eleven year old, the tar black

coffee the crew drank was untouchable, so during the flights I used to make up my liquids

from "accidentally opened" cases of soft drinks destined for the numerous Hudson

Bay Company stores or drilling camps in the North. Coke, especially, was my favorite. The

sugar and caffeine helped fight the motion sickness and fatigue. The next best cure was

chocolate bars and hard candy. I learned at an early age on how to survive as a bush

pilot.

The sight of Churchill was always welcome. The

trailer motel we stayed in had a bed to lie on and the food, I remember, was a relief from

the moose meat sausage, black bread, and hard baked pilot's biscuits, that was my father's

standard fare during our long flights in the bush. For an eleven year old, the tar black

coffee the crew drank was untouchable, so during the flights I used to make up my liquids

from "accidentally opened" cases of soft drinks destined for the numerous Hudson

Bay Company stores or drilling camps in the North. Coke, especially, was my favorite. The

sugar and caffeine helped fight the motion sickness and fatigue. The next best cure was

chocolate bars and hard candy. I learned at an early age on how to survive as a bush

pilot.

![]() During the many days we spent in Churchill,

waiting either for dispatch or weather, I drove a borrowed Honda 50 motorcycle. Obviously

under age, I would burn around the town and up and down the huge shipping docks waving to

dock workers and friendly Royal Canadian Mounted Police with impunity. I hung around the

blood soaked whale factory and ate real blubber. I climbed the rusty masts of the Russian

grain freighters, and at high tide rode out with the tug Twoilan to tow a grain

ship, the Warkworth, out to the mouth of the Churchill River. I scoured the ruins

of the Danish Fort, and we later crossed the river where I climbed on top the stone

ramparts of Fort Prince of Wales, finished in 1771 by the English.

During the many days we spent in Churchill,

waiting either for dispatch or weather, I drove a borrowed Honda 50 motorcycle. Obviously

under age, I would burn around the town and up and down the huge shipping docks waving to

dock workers and friendly Royal Canadian Mounted Police with impunity. I hung around the

blood soaked whale factory and ate real blubber. I climbed the rusty masts of the Russian

grain freighters, and at high tide rode out with the tug Twoilan to tow a grain

ship, the Warkworth, out to the mouth of the Churchill River. I scoured the ruins

of the Danish Fort, and we later crossed the river where I climbed on top the stone

ramparts of Fort Prince of Wales, finished in 1771 by the English.

![]() In one magical moment in Churchill, when I was

off exploring some rocky shore by myself, a lone harp seal surfaced right beside where I

was standing. We stared eye to eye for several moments until she seemed to turn away in

embarrassment and slip silently under the waters. Behind those big round moist eyes, I

sensed an intelligence and awareness that paralleled my own. I could never understand how

anybody could kill one of these creatures for profit. I have no arguments against those

who hunt animals for food or survival, but I could never condone hunting for profit or

pleasure. Not after looking into those eyes.

In one magical moment in Churchill, when I was

off exploring some rocky shore by myself, a lone harp seal surfaced right beside where I

was standing. We stared eye to eye for several moments until she seemed to turn away in

embarrassment and slip silently under the waters. Behind those big round moist eyes, I

sensed an intelligence and awareness that paralleled my own. I could never understand how

anybody could kill one of these creatures for profit. I have no arguments against those

who hunt animals for food or survival, but I could never condone hunting for profit or

pleasure. Not after looking into those eyes.

![]()

In

Churchill the

polar bears, although fascinating to me, were generally considered a nuisance. We

carefully worked our way around the bears that frequented the local dumps, and checked

around corners before wandering the streets. I was told of a little Eskimo boy eaten right

in Churchill. At times the fire trucks would be called in to hose the bears out of town.

Today, tourists come from all over the world to watch the polar bears. All in all, my

memories of Churchill, the Polar Bear Capital of the World, as it is now called, were of

wonderful times.

In

Churchill the

polar bears, although fascinating to me, were generally considered a nuisance. We

carefully worked our way around the bears that frequented the local dumps, and checked

around corners before wandering the streets. I was told of a little Eskimo boy eaten right

in Churchill. At times the fire trucks would be called in to hose the bears out of town.

Today, tourists come from all over the world to watch the polar bears. All in all, my

memories of Churchill, the Polar Bear Capital of the World, as it is now called, were of

wonderful times.

![]()

![]() Most of our time, however, was spent flying. The weather during the summer of

'66 was exceptionally good and every company in the north took advantage of it by trying

to cram six months of work into two. The Canso we flew, CF-IEE, was configured as a

freighter. My dad doesn't remember much about the history of CF-IEE, but it had the side

blisters removed. The gauges and engine instruments, which the flight engineer monitored,

were still located in the tower, but the throttle, prop, and mixture controls were between

the captain and co-pilot on the overhead console.

Most of our time, however, was spent flying. The weather during the summer of

'66 was exceptionally good and every company in the north took advantage of it by trying

to cram six months of work into two. The Canso we flew, CF-IEE, was configured as a

freighter. My dad doesn't remember much about the history of CF-IEE, but it had the side

blisters removed. The gauges and engine instruments, which the flight engineer monitored,

were still located in the tower, but the throttle, prop, and mixture controls were between

the captain and co-pilot on the overhead console.

![]() The Canso had an incredible fuel range and we

were able to cover huge areas of the arctic in a series of combined flights. We flew

regularly to the waters of Eskimo Point, Whale Cove, Rankin Inlet, Chesterfield Inlet,

Baker lake, Wager Bay, Repulse Bay, Resolute Bay, Igloolic, Pelly Bay, and others. Several

of these places, I believe, had gravel airstrips, but I recall landing on the water there

as well. Many times the land strips were too wet or soft to be used by the larger

aircraft, and the Canso would have to called in to operate off the water.

The Canso had an incredible fuel range and we

were able to cover huge areas of the arctic in a series of combined flights. We flew

regularly to the waters of Eskimo Point, Whale Cove, Rankin Inlet, Chesterfield Inlet,

Baker lake, Wager Bay, Repulse Bay, Resolute Bay, Igloolic, Pelly Bay, and others. Several

of these places, I believe, had gravel airstrips, but I recall landing on the water there

as well. Many times the land strips were too wet or soft to be used by the larger

aircraft, and the Canso would have to called in to operate off the water.

![]() On flights north out of Churchill we followed

the flat rocky western coast of the vast Hudson Bay. On many of the clear days we wandered

off-shore to spot Beluga whales congregating near the mouths of the larger rivers. The

Seal River estuary was one of our favorite places to watch the ghostly white whales

swimming lazily in small family groups along the coast. Early mariners called them the

"canary of the sea" because of their shrill cries. Bowhead whales, hunted during

the 60's, can once again be seen in the Eastern Arctic waters.

On flights north out of Churchill we followed

the flat rocky western coast of the vast Hudson Bay. On many of the clear days we wandered

off-shore to spot Beluga whales congregating near the mouths of the larger rivers. The

Seal River estuary was one of our favorite places to watch the ghostly white whales

swimming lazily in small family groups along the coast. Early mariners called them the

"canary of the sea" because of their shrill cries. Bowhead whales, hunted during

the 60's, can once again be seen in the Eastern Arctic waters.

![]()

In

places like

Repulse Bay and Igloolic we often anchored the big flying boat in deeper water. We

then would have a boat bring us to shore. In Wager Bay, our Eskimo boat driver took us on

a long tour along the coast. He told us that the day before they had seen polar bears

swimming across the bay, but, although I strained my eyes looking, we were not lucky

enough to spot them again. We did spot plenty of ringed seals, the polar bear's favorite

prey, basking in the sun along the unmelted fragments of sea ice that last well into the

height of the arctic summer.

In

places like

Repulse Bay and Igloolic we often anchored the big flying boat in deeper water. We

then would have a boat bring us to shore. In Wager Bay, our Eskimo boat driver took us on

a long tour along the coast. He told us that the day before they had seen polar bears

swimming across the bay, but, although I strained my eyes looking, we were not lucky

enough to spot them again. We did spot plenty of ringed seals, the polar bear's favorite

prey, basking in the sun along the unmelted fragments of sea ice that last well into the

height of the arctic summer.

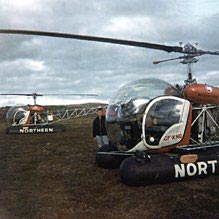

![]() Mining exploration was booming in the Arctic

and several companies, including Inco and Norando, had exploration crews in the field.

Many exploration and drilling crews further inland were supplied by small fixed wing

aircraft equipped with oversized tundra tires, but those near waterways could be serviced

by floatplanes or flying boats. On one charter we were called out to deliver drums of

aviation fuel for a survey party in an area near Nejanilini and Baralzon Lake. We landed

the big freighter once in Nejanilini and once in Baralzon to drop off the 45 gallon fuel

drums into the water where they were floated to shore. The fuel was to supply several

Northern Helicopter Bell 47s operating for Geodetic Surveys.

Mining exploration was booming in the Arctic

and several companies, including Inco and Norando, had exploration crews in the field.

Many exploration and drilling crews further inland were supplied by small fixed wing

aircraft equipped with oversized tundra tires, but those near waterways could be serviced

by floatplanes or flying boats. On one charter we were called out to deliver drums of

aviation fuel for a survey party in an area near Nejanilini and Baralzon Lake. We landed

the big freighter once in Nejanilini and once in Baralzon to drop off the 45 gallon fuel

drums into the water where they were floated to shore. The fuel was to supply several

Northern Helicopter Bell 47s operating for Geodetic Surveys.

![]() After delivering the fuel, the pilots invited

us to join them on a fishing expedition up the Baralzon river. The day was cold and

dreary, but the fishing was spectacular. In a matter of minutes I caught several master

angler sized arctic grayling. At age eleven, fishing was my life and to catch and hold

these ancient arctic species sent a hundred thousand year old chill down my spine.

After delivering the fuel, the pilots invited

us to join them on a fishing expedition up the Baralzon river. The day was cold and

dreary, but the fishing was spectacular. In a matter of minutes I caught several master

angler sized arctic grayling. At age eleven, fishing was my life and to catch and hold

these ancient arctic species sent a hundred thousand year old chill down my spine.

![]() The flight in the helicopter was a trip through

evolutionary time. In this latest wonder of technology, we flew low over the tundra,

exploring everything unusual that caught our attention. And the pilots knew what to look

for. We hovered low over herds of barren land caribou, we followed arctic fox as they

trotted along nervously looking over their shoulder, we watched arctic hares and ground

squirrels as they dashed about, and admired the graceful flight of the snowy owls.

The flight in the helicopter was a trip through

evolutionary time. In this latest wonder of technology, we flew low over the tundra,

exploring everything unusual that caught our attention. And the pilots knew what to look

for. We hovered low over herds of barren land caribou, we followed arctic fox as they

trotted along nervously looking over their shoulder, we watched arctic hares and ground

squirrels as they dashed about, and admired the graceful flight of the snowy owls.

![]()

The most

exciting event for me was coming upon a lone tundra wolf. She was a white-yellow in

color with long spindly legs, that kept her loping along at a terrific rate. We followed

her for a short while across the rolling sand eskers. The hair on my arms and back of my

neck stood up as she snarled and bared her teeth. I had a small cheap box camera, of which

I was quite proud, and from which I could take wonderful photographs. In the excitement of

any given moment, however, my father would always snatch the camera from me to snap the

"important" pictures. These pictures would inevitably turn out off-center and

shaky, but still today you can make out that prehistoric look of aversion on the wolf's

skulking countenance.

The most

exciting event for me was coming upon a lone tundra wolf. She was a white-yellow in

color with long spindly legs, that kept her loping along at a terrific rate. We followed

her for a short while across the rolling sand eskers. The hair on my arms and back of my

neck stood up as she snarled and bared her teeth. I had a small cheap box camera, of which

I was quite proud, and from which I could take wonderful photographs. In the excitement of

any given moment, however, my father would always snatch the camera from me to snap the

"important" pictures. These pictures would inevitably turn out off-center and

shaky, but still today you can make out that prehistoric look of aversion on the wolf's

skulking countenance.

![]() At one site we found plenty of caribou antlers.

As they shed them each year there were many remnants laying around. Because antlers are

such an important source of calcium and minerals for the arctic animal, it is unusual to

find antlers that have not been chewed into pieces. I was lucky enough to find one antler

in good shape. I carried that trophy home like a prize and kept it for many years, along

with my skull collection, until my mother found an excuse to throw my entire "bone

yard" out.

At one site we found plenty of caribou antlers.

As they shed them each year there were many remnants laying around. Because antlers are

such an important source of calcium and minerals for the arctic animal, it is unusual to

find antlers that have not been chewed into pieces. I was lucky enough to find one antler

in good shape. I carried that trophy home like a prize and kept it for many years, along

with my skull collection, until my mother found an excuse to throw my entire "bone

yard" out.

![]() The area around Baralzon

Lake has now been designated as an ecological preserve, because of its high concentration

of subarctic plant and animal life. In fact, the Qamanirjuaq Caribou herd which migrates

through the Nejanilini and Baralzon area has recently been estimated at almost 500,000

strong and growing. The sight of such a vast movement of large mammals is a spectacular

event unequaled in few places in the world.

The area around Baralzon

Lake has now been designated as an ecological preserve, because of its high concentration

of subarctic plant and animal life. In fact, the Qamanirjuaq Caribou herd which migrates

through the Nejanilini and Baralzon area has recently been estimated at almost 500,000

strong and growing. The sight of such a vast movement of large mammals is a spectacular

event unequaled in few places in the world.

![]() One of the contracts Transair had that

summer season, was to move Eskimo children back and forth from their homes to the

residential schools of Chesterfield Inlet. At summer's end, we started the flights to

return the children to the residential school. I remember the strong smell of their

greased bodies and animal hide clothes as we picked them up from the various settlements.

For the most part they wore modern clothes purchased from the Hudson Bay Company, but the

vestiges of traditional fur collars and seal-skin clothing could still emit a strong

enough raw odor to make you wince.

One of the contracts Transair had that

summer season, was to move Eskimo children back and forth from their homes to the

residential schools of Chesterfield Inlet. At summer's end, we started the flights to

return the children to the residential school. I remember the strong smell of their

greased bodies and animal hide clothes as we picked them up from the various settlements.

For the most part they wore modern clothes purchased from the Hudson Bay Company, but the

vestiges of traditional fur collars and seal-skin clothing could still emit a strong

enough raw odor to make you wince.

![]()

I

felt a strong empathetic bond for these Eskimo children. Many were my age or

younger, being forced from their family homes by some government dictate to live in

residential hostels for the sake of a foreign culture's idea of an education. The fear in

the eyes of the younger children as they boarded the Canso was real. I remember the

children getting motion sickness during the flight and throwing up in waves. I often

threw-up in sympathy on those flights, hiding in the galley so the kids wouldn't see me

getting sick.

I

felt a strong empathetic bond for these Eskimo children. Many were my age or

younger, being forced from their family homes by some government dictate to live in

residential hostels for the sake of a foreign culture's idea of an education. The fear in

the eyes of the younger children as they boarded the Canso was real. I remember the

children getting motion sickness during the flight and throwing up in waves. I often

threw-up in sympathy on those flights, hiding in the galley so the kids wouldn't see me

getting sick.

![]() On the back-hauls we carried drums of fuel;

dumping them right out of the floating flying boat to drift to shore where the locals

pulled them out. On a hot day in Repulse Bay, we actually went swimming amongst the

remaining fragments of ice floe after watching naked brown Eskimo children playing in the

water. The co-pilot, my father, and myself stripped to our underwear and jumped into the

frigid water from the rear cargo door opening. The effect I remember was like watching a

slow motion video of me jumping into the icy cold salt water and playing the video in

reverse with me coming out so fast that I did not even get wet.

On the back-hauls we carried drums of fuel;

dumping them right out of the floating flying boat to drift to shore where the locals

pulled them out. On a hot day in Repulse Bay, we actually went swimming amongst the

remaining fragments of ice floe after watching naked brown Eskimo children playing in the

water. The co-pilot, my father, and myself stripped to our underwear and jumped into the

frigid water from the rear cargo door opening. The effect I remember was like watching a

slow motion video of me jumping into the icy cold salt water and playing the video in

reverse with me coming out so fast that I did not even get wet.

![]() I remember being cold and wet and sick many

times. During rough turbulent weather the water leaked into the Canso everywhere. One of

my jobs was to ensure the bilge pumps were working properly, and I would often get soaked

in the process. I treasured my down-filled five star sleeping bag, because no matter how

wet I got, or it got, the down would still keep me warm. I would find a place amongst the

cargo or in the galley just behind and below the flight deck and curl up inside its cozy

warmth.

I remember being cold and wet and sick many

times. During rough turbulent weather the water leaked into the Canso everywhere. One of

my jobs was to ensure the bilge pumps were working properly, and I would often get soaked

in the process. I treasured my down-filled five star sleeping bag, because no matter how

wet I got, or it got, the down would still keep me warm. I would find a place amongst the

cargo or in the galley just behind and below the flight deck and curl up inside its cozy

warmth.

![]() Partly to give me a break from the ordeal of

day to day bush flying, my father would leave me in places like Repulse Bay or

Chesterfield Inlet for days at a time. Once when the Canso was dispatched on a particular

long and grueling trip, including a stop in Pelly Bay, I stayed with a French Canadian

Catholic father in Chesterfield Inlet who taught and preached in the native residential

school. He was kind enough, but very stern. His policy was not to interfere and my policy

was not to be interfered with. So we got along. I got into fights with the Eskimo kids my

age, who saw me as an alien. I befriended other Eskimo boys who found we shared a common

interest in guns and hunting. It was in Chesterfield that I had a first hand experience of

the conditions the children were subjected to as they had to spend most of their school

years away from their homes and their families. I was appalled. I could not imagine having

to do the same.

Partly to give me a break from the ordeal of

day to day bush flying, my father would leave me in places like Repulse Bay or

Chesterfield Inlet for days at a time. Once when the Canso was dispatched on a particular

long and grueling trip, including a stop in Pelly Bay, I stayed with a French Canadian

Catholic father in Chesterfield Inlet who taught and preached in the native residential

school. He was kind enough, but very stern. His policy was not to interfere and my policy

was not to be interfered with. So we got along. I got into fights with the Eskimo kids my

age, who saw me as an alien. I befriended other Eskimo boys who found we shared a common

interest in guns and hunting. It was in Chesterfield that I had a first hand experience of

the conditions the children were subjected to as they had to spend most of their school

years away from their homes and their families. I was appalled. I could not imagine having

to do the same.

![]() In Chesterfield I also

watched local artisans working on their carvings of soapstone and ivory. There were

certainly genuine artists in Chesterfield Inlet and in the other Eskimo communities, but I

couldn't afford their work. The carvings I bought were made, not by the true artists, but

by the average guy just trying to cash in on a growing industry. I bought the shoddy

discards for one dollar each. There was already, in 1966, a sorting out of who had it and

who did not. It was easy to see, even at eleven, the difference between the good and the

great. The carvings I bought were rough and scraped and awkward. By the time I returned

home, however, I had quite a collection of Eskimo carvings.

In Chesterfield I also

watched local artisans working on their carvings of soapstone and ivory. There were

certainly genuine artists in Chesterfield Inlet and in the other Eskimo communities, but I

couldn't afford their work. The carvings I bought were made, not by the true artists, but

by the average guy just trying to cash in on a growing industry. I bought the shoddy

discards for one dollar each. There was already, in 1966, a sorting out of who had it and

who did not. It was easy to see, even at eleven, the difference between the good and the

great. The carvings I bought were rough and scraped and awkward. By the time I returned

home, however, I had quite a collection of Eskimo carvings.

![]() True art, sculptured soapstone or ivory or even

bone, captures an idea or a moment in time. The feelings invoked: love or joy or despair,

are real and can be passed on by just touching or sharing the artifact. That tactile

concrete aspect of Eskimo art can pass on the stories even without the telling. The art is

the story. The art is the telling. I did not understand that back in 1966, but I

understand it now. The time from past to present is a journey from which you can learn.

But, the story of the journey has to be told.

True art, sculptured soapstone or ivory or even

bone, captures an idea or a moment in time. The feelings invoked: love or joy or despair,

are real and can be passed on by just touching or sharing the artifact. That tactile

concrete aspect of Eskimo art can pass on the stories even without the telling. The art is

the story. The art is the telling. I did not understand that back in 1966, but I

understand it now. The time from past to present is a journey from which you can learn.

But, the story of the journey has to be told.

Here in these pages, the story becomes

the art.

The story of the journey.

![]() In Virtual Horizons

we hope to publish the best that bush flying has to offer. The stories don't always have

to be written with, in the terms of a self published pilot author, "ten dollar

words," in order to tell the tale. We want everyone who has a story to tell about

bush pilots or the people who kept them aloft, to have a venue in which to share

our aviation heritage.

In Virtual Horizons

we hope to publish the best that bush flying has to offer. The stories don't always have

to be written with, in the terms of a self published pilot author, "ten dollar

words," in order to tell the tale. We want everyone who has a story to tell about

bush pilots or the people who kept them aloft, to have a venue in which to share

our aviation heritage.

![]() After the hormones of early manhood had

ravished my teenage brain, I lost for many years the incredible sense of wonder that my

first trip into the Canadian Arctic had invoked in me. Little can compare to that

impressionable age in a child's life, somewhere between 9 and 12 years old, when

curiosity, awareness, and wonder make the whole world, even a pond in your backyard, a

special place to explore. That age is our desperate eleventh hour, our zenith, and like so

many others, I have spent most of my adult life trying to win that feeling back.

After the hormones of early manhood had

ravished my teenage brain, I lost for many years the incredible sense of wonder that my

first trip into the Canadian Arctic had invoked in me. Little can compare to that

impressionable age in a child's life, somewhere between 9 and 12 years old, when

curiosity, awareness, and wonder make the whole world, even a pond in your backyard, a

special place to explore. That age is our desperate eleventh hour, our zenith, and like so

many others, I have spent most of my adult life trying to win that feeling back.

Article and Images by John S Goulet

![]()

In that light,

Virtual Horizons will be honored to bring to you one

of Canada's best aviation writers, as he searches for meaning and fulfillment

during an adventure packed flying career. A writer who graced the pages of Canadian

Aviation magazine for many years, and who has published an exciting account of his

varied bush flying past, Robert S. Grant will be with us on our virtual

journey. As an internet

exclusive, we will be printing excerpts out of Robert's book:

In that light,

Virtual Horizons will be honored to bring to you one

of Canada's best aviation writers, as he searches for meaning and fulfillment

during an adventure packed flying career. A writer who graced the pages of Canadian

Aviation magazine for many years, and who has published an exciting account of his

varied bush flying past, Robert S. Grant will be with us on our virtual

journey. As an internet

exclusive, we will be printing excerpts out of Robert's book:

Bush Flying: the Romance of the North.

![]()

Top of this story.

First time visitors restart with the Virtual Horizons entry page, or click on the adjacent attitude indicator to skip directly to more of our exciting stories

Posted on May 30th, 1996.

© Virtual Horizons, 1996.