Eye of the Elephant:

Mark

Became a Bush Pilot for a Reason.

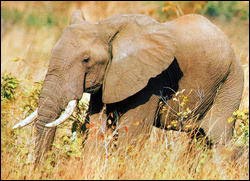

To Help Save the

Africa Wildlife

![]()

"If we don't do

anything when elephants are killed, we might as well not be here. And the plane is our quick response tool."

![]()

We tell Mulenga that the scouts

refuse to patrol unless they have at least six rifles per squad; so we

have collected the few serviceable guns scattered among the five scout

camps and concentrated them at Mano. He gives us four more firearms

belonging to Mpika scouts, who never patrol anyway. Mano will now have

thirteen rifles. By joining forces with men from Nsansamina and Lufishi,

they will have enough manpower and rifles to field two patrols, with

one-armed scout left over to guard the main camp. After loading the rifles

into the truck, we drive back to Mano.

We tell Mulenga that the scouts

refuse to patrol unless they have at least six rifles per squad; so we

have collected the few serviceable guns scattered among the five scout

camps and concentrated them at Mano. He gives us four more firearms

belonging to Mpika scouts, who never patrol anyway. Mano will now have

thirteen rifles. By joining forces with men from Nsansamina and Lufishi,

they will have enough manpower and rifles to field two patrols, with

one-armed scout left over to guard the main camp. After loading the rifles

into the truck, we drive back to Mano.

As we give the scouts their guns, we

announce new rewards for every poacher convicted and for each firearm and

round of ammunition taken in the national park. If a patrol captures even

five poachers, each scout will earn an extra month's pay. The money

offered by the new warden to build houses for the scouts has curiously

disappeared. So we hire poachers from Chishala and Mukungule to do the

job.

"This is a very fine thing you

have done for us, Mr. Owens. Ah, now you shall see us catch

poachers!" exclaims Island Zulu as we shake hands with the scouts.

Before we begin the three-hour drive back to Marula-Puku, Zulu leads me to

his private sugarcane patch, where he cuts a very large stalk for us to

chew during our journey. When we finally drive away from Mano, all the

scouts and their children follow us to the river crossing. Standing on the

far bank, they wave until we are lost among the hills and forests of the

scarp. At last, now that we have equipped the scouts, improved their camp,

given them guns and incentives, we feel we have a chance of taking the

park back from the poachers.

A ring of fire like a dragon's eye

leaps from the dark woodland below my port wing tip. I pull the plane into

a hard left bank and shove its nose into a dive. As we near the blaze I

can make out about thirty individual fires. It looks as if a small army is

bivouacked at the edge of the woodland. Poachers with a camp that size

will have sixty or seventy unarmed bearers and two or three riflemen, each

armed with military weapons Kalashnikov AK47s, LMG-56s, G-3s, and others.

They could easily shoot down the plane.

With me is Banda Chungwe, senior

ranger at Mpika. We have been on an aerial reconnaissance of the park to

plan roads and firebreaks. I have purposely delayed our return to the

airstrip until the last few minutes of daylight, so that we can spot any

meat drying fires the poachers may be lighting along the river. And seeing

poachers in action may light a fire under Chungwe. Although he is in

charge of overall field operations, this meek and mild-mannered man has

never ordered the scouts on a patrol or done anything to inspire or

discipline them. According to them, until today he has never even visited

their camps or the national park. They need his leadership badly.

I pull off the power and drop the

plane's flaps, checking my altimeter and taking a compass bearing on the

fires. Then I take Zulu Sierra down over a grassy swale below the canopy

of the woodland. Flying ten feet above the ground, I track the trail of

gray smoke from the dragon's eye. Just before the poachers' camp, I check

back on the stick, nip up over the trees, and chop the power. The camp

with its blazing fires is in front of us and a little to the right. I drop

the starboard wing and ease on a bit of left rudder, side-slipping the

Cessna for a better view of the camp below and so that any gunfire will, I

hope, go wide of its mark.

I can see several dozen men hunkered

around the fires, and three large meat racks made of poles one at least

ten feet long and four feet wide. On these giant grills, huge slabs of

meat are being dried over beds of glowing coals. 'Nearby lies the

butchered carcass of an elephant. Its dismembered feet, trunk, and tail

have been pulled away from its body.

"You sons of bitches!" I

swear. The senior ranger says nothing. Less than two seconds later, the

camp is behind us. In the shadow of the escarpment darkness is falling

quickly after the brief dusk, and our grass airstrip is not equipped with

lights. I turn the knob above my head and a dim red glow illuminates my

flight and engine instruments. I am beginning to get the itch on the

bottom of my feet that comes whenever I am pushing things a bit too far in

the plane. I pour on the power and head up the Mwateshi to its confluence

with the Lubonga, then follow it to the lights of Marula-Puku. If I do not

look directly at the airstrip, I can barely make it out on the back of a

ridge a mile northwest of camp. We have about two minutes of dusk left,

just enough time to go straight in for a landing. I begin to relax a

little.

"You sons of bitches!" I

swear. The senior ranger says nothing. Less than two seconds later, the

camp is behind us. In the shadow of the escarpment darkness is falling

quickly after the brief dusk, and our grass airstrip is not equipped with

lights. I turn the knob above my head and a dim red glow illuminates my

flight and engine instruments. I am beginning to get the itch on the

bottom of my feet that comes whenever I am pushing things a bit too far in

the plane. I pour on the power and head up the Mwateshi to its confluence

with the Lubonga, then follow it to the lights of Marula-Puku. If I do not

look directly at the airstrip, I can barely make it out on the back of a

ridge a mile northwest of camp. We have about two minutes of dusk left,

just enough time to go straight in for a landing. I begin to relax a

little.

The strip of fading gray grows larger

in the plane's windshield. At three hundred feet I switch on the landing

light again. At first it blinds me, but finally some faint greenery begins

to register in its beam. The crowns of the trees off the end of the runway

look like broccoli heads, growing larger and larger.

Two hundred feet, one hundred fifty,

one hundred, fifty. As we soar over the end of the strip, I cut the power

and bring the plane's nose up to flare for the landing. All at once, big

green eyes reflect in the landing light. Just ahead, a herd of zebras is

grazing in the middle of the runway. A puku scampers under the plane,

inches from its main wheels.

Ramming in the throttle, I haul back

on the control wheel. The stall warning bawls as Zulu Sierra staggers into

the air, just clearing the backs of the cantering zebras. Biting my lip, I

force the plane away from the ground, banking around for another try at a

landing. But in the minute it has taken to perform this maneuver, my view

of the strip has been lost to the night.

We are on a downwind leg to an

invisible airstrip. I hold our heading for another two minutes, which at

8o mph should put us more than two and a half miles from the runway, then

I make a descending turn for the final approach.

I check my watch: the same time and

speed should get us back to the field. I force my hands to relax on the

controls and continue my descent from one thousand feet above the ground.

Flying blind, I feel MY way down

slowly and carefully, leaning forward, straining to see the ground with my

landing light. My feet are jumpy on the rudder pedals. Five hundred feet

per minute, down. Down.

The "broccoli" trees flash

below. I still cannot see the airfield. I ply the rudders back and forth,

swinging the plane and its landing light side to side, trying to pick up

the strip.

Two parallel lines snake beneath us.

Our track from the airstrip to camp! Lowering the nose, I hold the track

in my light until the grassy surface of "Lubonga International"

resolves out of the blackness. Pulling back on the throttle, I haul up on

the flap lever. How sweet the rumble of the ground under my wheels!

After parking the plane, we climb into

the Mog and race down the steep slopes to camp. Delia throws together some

black coffee and peanut butter sandwiches, and fifteen minutes later

Chungwe and I are in the Mog and battering up the track for Mano. I'm

going to need every drop of the coffee, for I've been driving and flying

since dawn, bringing the senior ranger to our camp for our two-hour survey

flight. But I'm eager. With their new equipment and the senior ranger

second in command only to the warden sitting next to me, the scouts will

have no excuse for not coming on this operation. It is one of the best

opportunities we've had to send a strong message to the poaching

community.

At 10:30 P.m. we roll into Mano and

stop before the new unit leader's squat house of burnt brick and metal

sheeting. As soon as John Musangu emerges from the darkened interior of

his n'saka, I tell him what we have seen and ask him to get his men ready

to come with us. He pauses for a moment, drawing hard on a cigarette, then

turns and shouts to the scouts in Chibemba. I wait for Chungwe to add

something, but he leans against the Mog in silence. The scouts in the

n'saka mill about, while others drift in from distant parts of the camp

and begin yelling angrily at Musangu. Finally, he tells the senior ranger

and me that they refuse to come unless our project pays them extra for

each night they are on patrol. I ask the senior ranger to explain to them

that patrols are part of their job, not an extra duty, and they are

already being paid for them. Instead, he turns and walks around the truck.

Grumbling, the men glare at me,

refusing to move. Nelson Mumba declares that it is too late at night to go

after poachers and walks back toward his hut. Neither the unit leader nor

the senior ranger orders him to return. Even though as a project director

and honorary ranger I have full authority over the scouts, I am reluctant

to pull rank on Chungwe.

I cannot understand the scouts'

behavior. Maybe they are afraid. "Look, gentlemen," I say,

"I've been tracking poachers from the air for a long time. By now the

two or three riflemen will have split up, each taking maybe fifteen or

twenty carriers with him to shoot more elephants. Most of the men you find

at the carcasses will be unarmed; only one or two will have guns. I can

land you no more than half a mile from them. And, hey, what about the

reward? An extra month's pay for every five poachers you catch."

Finally, an hour and a half after we

arrived, and with deliberate delay, Island Zulu, Tapa, and some others

collect their new packs and climb into the back of the Mog. Shortly after

midnight, with the scouts and their leader in the truck, we begin the

rough run back to our camp. At 2:3 0 A.M. We stop at the airstrip. The

scouts pour out of the back of the Mog and into a large tent we have set

up for them. I ask Musangu to have the men ready to go by four-thirty. He

nods, then disappears under the flap of the tent. Driving on to camp, I

slip into bed beside Delia to try to catch a couple of hours sleep.

But I can only lie on my back staring

into the dark. At dawn I will try to airlift fourteen men in five round

trips from camp to Serendipity Strip near the poachers. In the two and a

half years since I last landed there, floodwaters will have littered the

runway with ridges of silt, deadwood, trees, and rocks.

Delia and I argued about my making

this run just a few hours earlier, when she was standing at the old wooden

table in the kitchen boma, slicing bread for my sandwiches. When I told

her I planned to airlift the scouts to Serendipity Strip, she stabbed her

carving knife into the tabletop with a violent thonk.

"Damn it, Mark! If you go head to

head against these poachers, it's only a matter of time before they begin

shooting at you at both of us! They could sabotage the plane, or ambush us

in camp or anywhere along the track. We can't fight cutthroats like

Chikilinti by ourselves!"

"Look, I am not going to sit by

while these bastards blow away every elephant in the valley!" I

jabbed a stick into the campfire.

"But landing at dawn on a gravel

bar you haven't seen in two years? You'll kill yourself, and the scouts

won't go after the poachers anyway. That's just not smart."

"I'm not going to make a habit of

this," I said. "But if we don't do anything when elephants are

killed, we might as well not be here. And the plane is our only

quick-response tool." The next slice of bread Delia cut was about as

thick as my neck, and so ended the argument.

I have barely fallen asleep when the

alarm goes off. I roll over, choke the clock, and stare at its face. Four

in the morning. I stumble into my clothes and out the door. As I pass the

office, I grab my red "life bag" full of emergency food and

survival gear, then hurry along the dark footpath toward the kitchen.

Delia stands there bathed in a halo of yellow-orange firelight, cooking up

whole-grain porridge, making sure that if I die this morning, at least I

will be well fed. A few quick spoonfuls, a swig of stiff coffee, a hurried

kiss and I am on my way to the airstrip.

In the Mog I climb the steep side of

the ridge below the airfield. Out my window to the east, the sky is

sleeping in starlight, soon to be awakened by the dawn. And so are the

game guards when I reach the airstrip.

"Good morning, gentlemen," I

shout into the tent. "Let's go. The poachers are already on the

move." They struggle to their feet, rubbing their eyes, stretching

and yawning.

I circle Zulu Sierra, flashlight in

hand, untying, unchocking, and checking her for flight. Pulling the hinge

pins, I remove the door from the right side and all the seats but mine, so

I can squeeze in as many scouts as possible.

"I'll take the three smallest

scouts, their rifles and kits on the first trip," I shout to Musangu.

"Four more should be ready to go by the time I get back, about twenty

minutes after we take off." I will keep the plane as light as I can

for the first landing, until I have checked out Serendipity Strip. Still

rubbing sleep from their eyes, three scouts shuffle to the plane,

shirttails out, boots untied and gaping. I turn back to the plane to do my

final checks.

I pull the bolts on each of their

rifles to check that they are unloaded, then board the three scouts,

seating each on his pack and securing him to the floor with his seat belt.

I climb in, crank up, and begin

warming up Zulu Sierra's engine. While waiting for the first light of

dawn, I give the scouts their last instructions. "Okay guys, we'll

fly low along the river, so that we won't be seen. When I have all of your

group there, I'll fly over your heads to show you the way to the poachers.

Follow the plane. Get going fast, because they will head for the scarp at

first light. While you are moving up, I'll try to pin them down by

circling over their carnp."

As soon as the stars in the eastern

sky begin to pale with the dawn, I take off and turn onto a heading of one

five zero.

Seven minutes after takeoff we are

slicing through puffs of mist hanging above the broad, shallow waters of

the Mwaleshi River. The gravel crescent of Serendipity Strip lies just

ahead. I pull off power and put down three notches of flap, going in low

and slow, the grass heads clipping the main wheels as I look for anything

that might trip us up on landing. The plane's controls feel mushy at such

a low airspeed and I need plenty of throttle to keep from stalling into a

premature touchdown.

Gripping the control yoke hard with my

left hand, I slowly bring back the throttle. Zulu Sierra begins to sink.

The grassy, uneven ground, littered with sticks, rocks, and buffalo dung,

flashes underneath the wheels. The stall warning blares. The end of the

short gravel bar looms ahead. I can't find a good spot to touch down, so I

ram the throttle to the panel and haul the plane back into the air.

On my third pass over the area I

finally see a clear way through the rubble on the ground. This time I

bounce my wheels and the plane shudders. But they come free without any

telltale grab that would indicate a soft surface. Once in Namibia I tried

a similar trick, and when the wheels stuck in a soft pocket of sand the

plane flipped on its nose, burying the prop and twisting it to a pretzel.

The next time around I ease the plane

onto the grass. As soon as the wheels are down, Zulu Sierra bucks like a

mule, her wishbone undercarriage flexing. I stand on her brakes and we

slide to a stop with less than a hundred feet to spare before the

riverbank. The three scouts laugh nervously and immediately crowd through

the open door of the plane. I grab the first by his shoulder. "Don't

walk forward or the prop will chop you to pieces." He nods his head

and they are out.

Four trips later all the scouts are at

Serendipity. Standing under a tree near the river, they wave cheerily as I

fly over, heading for the spiral of vultures and the cloud of smoke that

mark the poachers' camp little more than half a mile away. I come in low,

dodging the big birds, and side-slipping the plane to avoid being shot. I

cannot yet see the camp, but the sickly sweet odor of decaying meat the

honey of death washes through the cockpit. And there it is, the rack -no,

six racks, covered with thick slabs of brown meat- the fires, and the men,

at least fifteen of them, naked to the waist, covered with gore.

Flashing over the camp, I yank Zulu

Sierra around and drop to the grass tops, bearing down on a gaggle of

eight to ten poachers who are running away. I lower my left wing, pointing

it at them, holding a steep turn just above their heads. They flatten

themselves to the ground and stay put. Still circling, I climb out of

rifle range and switch on the wing-tip strobe lights, signaling to the

scouts that I am over the poachers. Far below, a spiral of vultures lands

on the cache of meat, devouring it in a frenzy.

For the next hour I orbit high and low

over the poachers, waiting for the scouts to arrive. Finally, I have to

break off and return to camp for fuel. After refueling, I write out

messages describing the number and location of the poachers and stuff them

in empty powdered-milk cans from the pantry. I add pebbles to each can for

ballast and attach a long streamer of mutton cloth. Then I take off again

and fly over the camps at Lufishi, Nsansamina, and Fulaza, dropping the

tinned messages to the scouts there. The poachers will have to pass

through or near those camps to get out of the park. It should be easy for

the scouts to cut them off.

By the time I land back at Marula-Puku

I have been flying for almost six hours. Numb with exhaustion, I wince as

I calculate that I have just burned up two hundred dollars worth of fuel.

But it will be worth it if the scouts can capture twenty or thirty

poachers.

Others will think twice about shooting

elephants in North Luangwa, and maybe some will accept the employment and

protein alternatives that our project is offering them. For the first time

I feel confident that we are about to make a serious dent in the poaching.

Others will think twice about shooting

elephants in North Luangwa, and maybe some will accept the employment and

protein alternatives that our project is offering them. For the first time

I feel confident that we are about to make a serious dent in the poaching.

We have no radio contact with the

scouts and thus have no idea how the operation is going. Four days later

Mwarnba and I are fixing a broken truck at the workshop.

"Scouts," he says, pointing to a long line of men wending their

way toward us along the river south of camp. I shake hands with each of

the game guards as they arrive. With them are two old men and a

twelve-year-old boy dressed in tattered rags, their heads hanging,

handcuffs clamped to their wrists.

John Musangu steps forward. "We

have captured these three men.”

"This is all?" I ask.

"These are only bearers. What about the riflemen?" I have

already heard over the radio from the warden's office that the scouts from

the other camps have managed to catch only a single bearer.

"They escaped," Musangu

declares. He goes on to say that there were fifteen men and a rifleman in

this particular group. But except for these three, they all got away. The

operation has been a bust except that the airplane and the vultures have

denied the poachers their meat and ivory.

Island Zulu, the gabby old scout,

spreads his arms and begins soaring about, purring like an airplane as he

mimes the airlift; then, hunching over, he stalks through make-believe

grass, parts it, aims his rifle, and fires a shot. Turning in circles, he

feigns a tackle of one of the three poachers, now sitting on the ground,

scowling and rolling their eyes in disgust. Finally, a twinkle in his eye,

he predicts, "With ndeke, now poaching finished after one year!”

I drive the arresting officers and

their captives to the magistrate's court in Mpika. The boy is not charged.

Days later the two men captured in the operation are each fined the

equivalent of thirteen dollars and are set free.

|

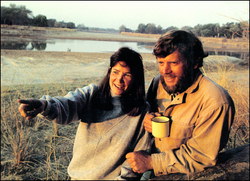

"Mark, I thought you were dead!..." "I am sorry, Boo. I just don't know what else to do. You know my flying is the only thing standing between the poachers and the elephants." "Yes, but I'm not sure this is worth dying for anymore... I want to stop poaching as much as you do, but you've crossed the line... |

|

To order your copy today click on the appropriate flag. |

| The Eye of the Elephant:

An Epic Adventure in the African Wilderness By Delia & Mark Owens |

![]()

Note from the Editor. These excerpts are presented in order to promote the sale of the book "The Eye of the Elephant." All text and images are copyrighted to the publisher. A link to the Owens Foundation for Wildlife Conservation can be found in the eBush Communications Page. Once you read this book you will know that any contributions made to the Owens Foundation are going to a good cause.

Use the attitude indicator as your guide back to Inside Africa.

Top of this story.

Last modified on

March 05, 2006 .

© Virtual Horizons, 1996.