PipeBaby

![]()

Float

Flying Adventures in the Niger River Delta

![]()

I was down by the jetty helping the Nigerian Engineer work out a intermittent problem on

the Turbo-Beaver, when a call came in on my walkie-talkie radio.

I was down by the jetty helping the Nigerian Engineer work out a intermittent problem on

the Turbo-Beaver, when a call came in on my walkie-talkie radio.

“X-ray November, X-ray November; Bonny One.”

“Yeah, go ahead Bonny One.”

“What’s your location?”

“I’m down by the airplane, do you need me to come-up?”

“No, but we got trouble in the swamp, would you be able to take Lamar out there right

away?”

“Yeah, just give me about 20 minutes to get the cowlings back on.”

“Fine, it will take them that long to get ready anyway. Thanks.”

“Alright, I’ll just standby the plane till they get here.”

“Fine.”

I turned to Tao and said, “You heard the man, let’s put her together.”

“But we never found the problem!” Tao complained.

“Don’t worry about it, it’s my problem now.”

Tao and I fastened the cowlings back on the engine and then Godfrey, my swamper and

dock-hand, swung the floatplane out of her protective berth to the outside of the ‘U’

shaped jetty. Here he topped up the fuel and connected the external power ready for when

Lamar and his crew came down.

Willbros, the company I flew for, had recently gotten a contract to put in a new swamp

pipeline for Agip Oil of Nigeria. The pipeline was large diameter pipe for pumping crude

from their newest producing wells in Ogbainbiri to their tank farm in Brass. I suspected

that the “trouble” had something to do with getting the construction equipment on site.

Ogbainbiri was a rainforest location deep inside the Niger River Delta. The only way to

access the site was by river. To get the equipment and pipe to the location it all had to be

loaded on to barges and then towed south down one river and north up another again and

again to traverse westward. Even the cranes had to go along to off load the pipe. The

whole mobilization could take days or even weeks.

This region of the delta was mostly flooded rainforest and swamp, with very little high

ground. What solid ground existed was usually land that had been dredged up by

previous oil sector work and immediately claimed by the nearest or most powerful village

for themselves to build shelters or plant crops on.

Furthermore, there was no developed

infrastructure in the delta. Everything was done on the water and any company expecting

to work in the area had to bring everything they needed with them, including

communications, transportation, and accommodations.

Most all the workers travelled to the swamp location by boat and lived there for as long

as it took to complete the contract or 6 months whichever came first. All the workers

lived on houseboats, communicated by radio, and got around by speedboat. Basically

there were three divisions of labour. There were the ex-pat dredging hands and pipeline

worker from Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi, and there were the national

surveyors, welders, mechanics, and fitters from Port Harcourt, and then there were the

local delta region labourers, security guards, and boat drivers from the nearby villages.

When anyone needed to get to the work site in a hurry, however, I would fly the

floatplane direct from Port Harcourt to land anywhere in the Niger Delta within 20-30

minutes of takeoff. The only catch was that with the tugs, and barges, and houseboats

being very mobile and the work always changing location, I really had to have some idea

where to find the people I was looking for before I departed.

That is where the HF radio came in. Peter, the radio operator, would call the tug or

houseboat attached to the work site and divine their location. I say “divine” because

depending on the work location radio operator this was not an exact science. The location

was usually given in relationship to some obscure river, creek, or village and it was my

job to figure out where they really were on the map. Even the advent of the GPS did not

help much because unless I had been there myself the locals did not know their own

coordinates. In fact, I believe if you had put a map of the world down in front of most of

the delta dwellers, they could not find Nigeria, let alone Ogbainbiri.

As I was waiting by the jetty, Gordon, the Operations Manager, drove down in his

Willbros red Blazer. Gordon, Scottish by blood but British by demeanor with a sharp wit

and a quick temper to match, would often drive up to whoever he needed to see in the

yard and sit in his Blazer, his left arm leaning on the open window and his right hand

holding the radio mike, until the person targeted walked up to pay homage to the

“bossman.” Gordon was in charge of the floatplane… and everything else.

This time Gordon stepped out from his air conditioned Blazer, leaving it running, and

came down to talk to me. Godfrey knew that was a sign to hide and slipped into

our engineering porta-cabin, and Tao followed quickly behind him. I could not imagine what I

could be in trouble for so I waited pretending not to see him walking down the gangway.

“John, did you get the ‘Beaver’ fixed?”

I had learned long ago that no one wanted to hear about a “broke” airplane just before

they went flying so I lied to him. “Yeah, just some bad fuel, no problem.” It was easy to

lie to most managers about the condition of the airplane as they expected you to.

“Great, hey… I’m going to send Lamar down with Troy… have you met Troy? He just

came in from the States. They can find out what is going on. We got a radio call saying

the pipe barges and Mr. Kurt were being held up near Apoi Creek. Peter says he thought

they were being boarded. But that jackass Peter can never get a message straight. I think

there is a houseboat with them. Just drop everybody at the houseboat and wait for

Lamar.”

I knew there was more to this than what Gordon was letting on as Lamar could have told

me all this.

“Oh, yeah,” he added as he headed back up the hill, “Don’t let the villagers get you, I

need the plane tomorrow.” That was the real message Gordon came to deliver.

Lamar was down shortly with a shit load of parts and tools that needed to get to the work

site. No sense wasting room on the plane. His swamper and Godfrey loaded it all in the

Beaver and the floats sunk a few inches. Lamar with his ever present Willbros issue

baseball cap was tall and thin with a complimentary sharp thin nose. His skin was

translucent like he was made of wax and you could make out the thin red veins tracing

their way across his face and down his sun burnt neck. He was a no-nonsense quiet kind

of boss who never told you to do anything, but rather asked you if it was ok. “John,

would it be alright if we took along a couple more hands, they just got in and I need them

to git to the laybarge.”

I could see a couple of red faced “good old boys” with coveralls and red suspenders to

match sitting in Lamar’s air-conditioned truck. I waved them over. More new guys. That

is not good. Willbros had some of their regular hands from the States drag-up and head

home just recently and we were now getting their replacements. I think Troy was

someone’s replacement as well. The “boys,” who weighed 300 lbs each if they weighed

an ounce struggled out of the truck and sunk the jetty as they crossed the gangway.

Since neither Troy nor the new boys had been on the floatplane before I gave them all a

briefing paying particular attention to letting them know how they were to disembark.

Like I said earlier there was no infrastructure in the delta and this meant either anchored

or drifting plane-to-boat transfers. As the rivers were often narrow and winding this

additionally meant that if the current or wind or tide was moving we had to be quick so

that the Beaver would not drift into the trees or up over a sand or mud bank before I

could get started up again. I had perfected the drift transfer method, but it often depended

on having a knowledgeable boat driver and experienced passengers. Today I could count

on neither.

I did not pay much attention to Troy, but I liked him right away. He was quiet and stayed

quiet, except for when he was winning at darts in the bar, and he wore a perpetual pulled

up smile that looked both smug and apologetic at the same time. Troy, throughout the

hottest time of the year or during the rainy season, always wore a baseball cap, a snap

button long sleeve western shirt, blue jeans and cowboy boots. I think he had more than

one pair of each, but I really don’t know. He always looked the same.

The Turbo-Beaver was not overly loaded and we got airborne in a hurry. It was heavy

enough, however, to affect my maneuverability and I would have to be careful at the

other end until I could off load my oversized passengers. I called the Airwork frequency

shortly after lift off, announced my traffic intentions, and climbed out to 2000 feet

heading west across the Delta. The Airwork radio operator read back my details and

added, “Alpha X-ray November, no reported traffic to affect your climb, report landing

Apoi Creek.” In other words, no reported traffic meant “no helicopters” as I was the only

floatplane in Nigeria.

Being September we were still in the rainy season, but getting closer to the end. The sky

was mostly cloudy but broken to the occasional bright blue patch with good visibility in-

between the numerous rain showers. Later in the afternoon the showers could build to

thunderstorms, but right now they were benign and friendly. I flew through the few

showers on my route just so I could hear the sound of the large drops drumming on my

windscreen and cabin roof.

After 30 minutes I picked up Apoi Creek about 40 miles from the

Atlantic coast and continued

downstream toward the ocean. I figured the barges, which were heading upstream, would

be somewhere about 20 miles down, but this way I would not miss them. Apoi Creek was

long and narrow and very winding. By setting my altimeter at sea level when previously

on the river and watching the altimeter when breaking through the canopy, I had

discovered that the trees in this part of the rainforest would often reach 200 feet with

some emergents topping 230 feet. The trees formed a vertical wall of green on each side

of the river making any attempt to see anything on the water from an angle impossible. I

needed to be directly overhead and going slow. I descended to 1500 ft to get a better view

into this rainforest ravine.

I found the barges along the river and sure enough the procession had come to an

unscheduled stop beside a particularly large village built on a rare area of high ground. I

slowed the Beaver down to 85 knots with climb flaps so I could get a better picture in my

head of what was going on. The lay barge was anchored upstream backed by the tug “Mr.

Wade.” Along side was a houseboat and behind them was the pipe barges held by the tug

“Mr Kurt.” These were followed up by the equipment barges which also appeared to be

anchored. The entire flotilla was bunched up in that narrow river making up an

impassible blockade.

When flying over a “trouble spot” and deciding whether or not to land, I had made up a

few hard and fast guidelines. For instance, “never land if there is unsubstantiated smoke”

like as if something has been set on fire. “Never land if there are groups of people

running around helter-skelter,” especially if one group appears to be chasing another.

“Never land if there are people laying on the ground” and don’t appear to be sleeping.

Those kind of guidelines. In this case, the scene below appeared calm with only a few

villagers milling around.

Lamar always sat in the seat behind to my right. He leaned forward and yelled (we had

headsets and an intercom, but these guys would not be caught dead using it) over the roar

of the Beaver, “They is shut down alright, could you wait for me?” He sat back and

emptied a big gob of chewed snuff into a cut-up water bottle.

“If you help me with the anchor,” I said. He nodded and looked down at the scene below.

I decide to land upstream from the laybarge where I could get Lamar and the boys near

the houseboat. The downstream side was tortuously winding and would be very difficult

to find a straight enough section to land on. That was where the village was as well and

the further away I anchored the better off I was. Even if the villagers were not hostile the

friendly visits from the local children could get vexing as they ended up crawling all over

the floats and stealing the little rubber squash balls that we used for bung stoppers.

On the upstream side, however, there was a straight run of about 200 meters which was

preceded by a slow 450 bend and another straight stretch of over 400 meters. I would line

up on the first section of the river and then fly my final about 50 feet asl around the bend

and then touch down on the final 300 meters. That would give me plenty of space to turn

around again and anchor the Beaver without getting too close to the laybarge.

I had only circled the jumbled convoy once and headed back upstream. I did not want the

villagers to figure out what I was doing. If you circle several times they would run for

their canoes and be launched and ready to paddle the second you touched down. If you

only went over once they would think that you had left. I would then do my approach so

as to sneak in before they realized I was there. That gave me time to drop my passengers

and escape if need be.

There was no wind and I only had the current left to assess. I flew my outbound leg close

to the river and had a good look. The water was high and swollen with recent rains, but it

did not look very swift. The center of the river was rippling like I expected of fast moving

water, but the water along both tree lined banks was glassy calm slowed by the friction of

the banks and the tree roots. After landing I would edge close to the bank to anchor in the

slower waters. I had anchored about 20 miles upstream in an adjacent river several days

ago without a problem so I left confident my anchor would hold here as well.

I initiated a 600

bank turn onto the first straight stretch using 65 knots and takeoff flaps.

Our speed was exaggerated by the proximity of the overhanging branches rushing past

the wing tips and the fact that I entered the valley of trees while still executing the

descending turn. My excuse for such dramatics was “a well practiced pilot was a safe

pilot.” If Troy, who was sitting beside me, was nervous he did not show it.

I checked my descent at about 50 feet above the river just in time to kick right rudder to

carve a tight turn around the blind bend and, keeping the right wing low, touch down with

the right float just as we came around the corner onto the straight stretch. The real reason

I kept the circuit in tight was because with this quick approach and landing there was no

chance a speed boat could start up and rush up the river in time to surprise me coming

around the corner. Timing is everything when you fly such tight margins. On touch down

I pulled beta, dumped my flaps, and kept the control column tight in my lap until I was

off the step and in displacement taxi.

The green blur slowed to a focus of leaves and foliage and I lowered the water rudders.

The laybarge was just ahead. I could see already that there was no room to taxi between

the laybarge and the houseboat and so I would have to anchor upstream no matter what. I

was heading up a dead end alley. The other factor was that there was not enough room to

complete a normal water rudder turn in the narrow channel. I could only be doing such a

maneuver in a turbine equipped aircraft as there was simply not enough room for doing

anything else except making use of the beta and reverse prop to get turned around and

into current.

So far there had been no movement from the barges. Specifically there were no speed

boats coming out to greet us. I began to realize that the laybarge was getting very close

very quickly. I had misjudged the speed of the current and I was running out of

maneuvering room. I later realized that being 20 miles closer to the ocean meant this part

of the river was being affected by the ocean tide. And

the tide was going out.

I was already on the right side of the river to prepare for my left turn, so I kicked left

rudder to get the nose going in the proper direction. When in a tight spot I always plan to

turn left to take advantage of the normal reactive forces of the aircraft prop, thrust, and

prop wash. My stomach churned when nothing happened. Because the Beaver was only

producing idle thrust it was not being propelled any faster than the abnormally fast

current. In other words, we were not moving relative to the water. The water rudders

were wholly ineffective.

I could not shut down as the current would crush us into the laybarge before I could get

the anchor to hold. I had no time to think. I instinctively, if applying physics

to a moving machine can be instinctual, knew I had to speed up our taxi relative to the speed of the

water. I had to add power.

With only a short distance between us and the laybarge I felt

like I was committing pilot-error induced suicide. I shoved the power lever ahead and

kept full left rudder to get the turn going. As the power increased and the heels dug

deeper the Beaver began an agonizingly slow turn toward the opposite bank. I could see

immediately that I was not going to make the turn in one go.

As soon as I got sideways across the channel and with only a couple of feet between the

prop and the bushes, I hauled full reverse, lifted the water rudders, and waited for the

turbine to spool up. We slowed and stopped and then with a rush of prop surge we

lurched backward in a cloud of prop spray. With 600 lbs of good old boys in the back the

heels dug in and began to submerge, all this happening faster than I could think. I could

feel the presence of the laybarge pulling in the million dollar Turbo-Beaver like a quark

to a strange attractor. The laybarge had me in a tractor beam.

The wings left the horizontal and began to list with the right wing

tip getting closer to the water. If the tip was to touch the water, the surface tension would suck the entire wing

under flipping the aircraft. But again, the water rudders would not be effective unless I

was to have backward momentum relative to the current. I had to have speed, and speed

was bringing me closer to the laybarge. I held in as much reverse as I could manage.

With only seconds before crunching into the barge I pushed the power lever forward,

lowered the water rudders, and kicked hard left rudder. The aircraft lurched forward

arching the right wing agonizingly close to the water, but clear of the bushes. I

straightened her out and the right float bobbed back to the surface and we were clear. The

tail must have missed the laybarge by inches as well. Mark that one up to experience.

Instead of making way, the floatplane just managed to hold ground against the brisk

current. I added power to move forward to a comfortable safe distance. To anchor I must

have enough room to leave a 180 foot lead, and then enough distance again so that when I

retrieved the anchor to depart I would have time to start the engine, allowing the turbine

to spool up and the prop to come out of feather, before drifting back into the barge behind

me. I gave myself double the normal distance because of the raging river and signaled

Lamar to go for the anchor.

Lamar crawled out on the left float to the float hatch and brought out the anchor. On my

signal, as I allowed the floatplane to drift backward slightly, I motioned for him to drop

it. The rope, attached to the inside of the float compartment with a u-bolt, spooled out as

the anchor sunk. The river was deep and I just circled my finger forward to signal that

Lamar should keep letting the rope out all the way. I needed as much scope as possible to

provide a good bite. Seven feet of rope for every one foot of water depth. I was always

surprised at how a good anchor did not have to be very big to provide a good hold, as

long as you had enough rope and it was set right.

Lamar gave the anchor a tug when it hit bottom and set it in deep. Before shutting the

engine down, I quickly gave Troy a lesson on water rudder management. I wanted him to

use the water rudders on his side of the aircraft to hold the nose straight in the current.

It

was easy. Right rudder for nose right and vice versa. I then pulled the engine condition

lever to idle-cutoff and feathered the prop. I would normally feather first, except I was

trying to minimize the forward surge from the prop.

With Troy on the water rudders, I jumped down on the float and Lamar handed me the

rope. I wanted to tie it on myself so only I would be responsible if the knot let go.

Although the rope end was fixed onto the left float, I had to tie the rope so that it would

pull from the center of the aircraft, preferable from below the engine. That kept the

aircraft true to the direction of pull from the anchor and would prevent the floatplane

from “hunting” or swinging from side to side in the current and consequently working the

anchor loose.

For that purpose I had bolted a stainless steel cable across the front of the floats. I could

walk on this cable, like managing a tightrope and then tie the anchor rope between two

brass swedges directly in the middle of the cable. This knot had to be secure from the

anchor side, but easy to untie from the aircraft side. Moreover, with the cable being low

to the front of the floats, the stronger the current the more the draught of the anchor

would pull the aircraft’s nose further down and lift the heels of the floats further out of

the water reducing the force of the flow around the rudder area and allowing the aircraft’s

center of buoyancy to move forward and to stay true as well. For all this the water

rudders must be up while on anchor.

This technical knowledge involved in setting an anchor for a floatplane in a narrow river

with a strong current was not anything I had been taught, but something I had learned

while on the job. And I messed up several times during the learning process. Luckily I

had never damaged any part of an aircraft during this process and I was not about to start

this day.

With the floatplane safely on anchor, I stood up and leaned against the wing strut looking

back toward the lay barge. I could now see some bodies moving around the houseboat

and within a few minutes a “flyboat,” as we called the speedboats, emerged and started

toward the aircraft. As he drew closer we could see the driver was not alone. Inside the

boat were several muscular young men presumably from the village coming to greet us.

Lamar spat a large glob of snuff into the river and let out a long expressive, “Sheeeiit.”

Villagers in the work boat could only mean trouble.

As they pulled alongside the driver told Lamar that these men were representing the

village and that they needed the “boss man” to come with them and talk to the Chief. In

this case, that would be Lamar. Lamar got in the boat and motioned the others to join

him, but the villagers refused to let them on. “Only the boss man,” they insisted. Lamar

said he would send the speed boat back for them.

Lamar gave me a resigned frown like he had just been turned down by the last

hooker in the bar and added, “Keep your radio on.”

I proceeded to make myself comfortable by latching open the aircraft doors to let the

breeze meander through the cabin. The two big old boys were sweating anyway

Troy asked me if the villagers made a habit out of stopping the work barges. I explained

that the villagers did what they could to disrupt the work in order to extract some type of

payment for themselves or their Chief. Usually a superintendent, like Lamar, would

negotiate a payoff price and the work would continue. Sometimes, if things got nasty, the

village would hold some of our workers for ransom in order to push the price higher.

Troy thought about that for a minute and asked, “Have you ever been held hostage?”

“Yeah, a couple of time. They usually get me while I am driving, but they have never

gotten me with the plane. I am usually pretty careful.”

I few minutes later Lamar called me on the walkie-talkie. “X-ray November, come in

John.”

“Go ahead Lamar,” I answered.

“You’d better take the boys and git out of here. They got women and babies all over the

damn laybarge, and the flyboat driver says they are talking about gitting the plane. You’d

better go.”

“What about you,” I ventured.

“I’m fine, just tell Gordon to send Andy, I need some help to talk to these people.” Andy

was our company lawyer and public relations negotiator. He was old and slow, but he

usually got us out of these national binds.

No sooner than I had put the radio down than I saw a wall of canoes coming from

between the house boat and the laybarge. It took me a minute to realize that they were

coming around the laybarge from the village down the river. It had taken them this long to make it to this far,

but there was no doubt they were coming to take the Beaver. I did not have long.

“Back in the plane, we have to get out of here, now! Get in and close the doors. Troy get

on the water rudders and hold the nose straight while I pull the anchor.” Troy jumped into

his seat while I put the water rudders down into the slipstream of the current where they

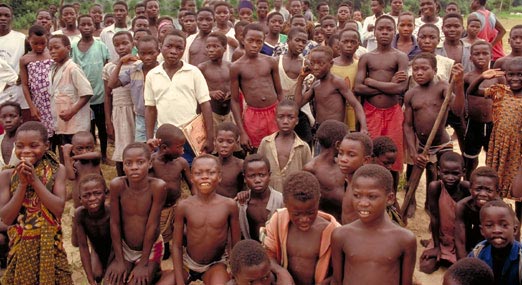

would be most effective. I looked back and saw about 20 canoes filled with 4-5 bare-chested occupants each paddling furiously against the raging current in an attempt to

prevent our escape.

I yanked on the anchor rope and where the loop would normally pull free and release my

self designed knot, it never budged. “Shit.” I pulled harder, but realized that the fast

current had tightened the knot beyond where it could be considered a reverse slip knot. I

had to release the pressure of the current before I could untie the knot. I thought of

cutting the rope, but I really hated losing my anchor. A good anchor is hard to find. I

decided to start the engine first and allow the exhaust thrust to push us forward enough to

relieve the tension. The prop was ahead of where the cable was strung and I could reach

in under the cowling and untie the rope with one hand from behind the swinging prop.

Troy would have to keep steering.

I looked back and the paddlers were closing the gap. Watching the natives with their

muscular backs arched in unison and their red-black sinewy muscles powering the canoes

forward, I envisioned a tribe of savage natives attempting to capture the “sweet as

chicken” white man, strip him naked and have the women of the village whip him with

switches. That wasn’t a vision, that was the reality. Several of our expat workers had been humiliated in such a manner.

They continued unabated struggling against the current. I jumped into my seat, flipped

the battery switch, and hit the starter. Nothing.

No whine, no click click click, no clacking. Nothing. “Shit. Not again.” I had forgot

about the problem we had been having. Every 5th or 6th start the starter contactor would

freeze and prevent the starter from energizing. Tao and I had changed the contactor a few

days before, but after several starts the problem had reoccurred. That morning we had

been looking for the cause, when Gordon called. In the rush to get away from the ensuing

canoes I had forgot that I was not going to allow a drift start anyway. I had wanted to

start on anchor and only retrieve the anchor from under the floatplane once under way. I

could do this by myself while in feather or I could enlist someone to help with the

rudders. Luckily the knot had stopped me from attempting a drift start or we would have

ended up as a crushed beer can under the laybarge.

Being a “guest’ in the village looked a better fate and more likely as the canoes got

closer. Actually being held hostage by the villagers wasn’t life and death unless you died

of diarrhea or dysentery from eating their food or drinking their water, or died of malaria

after getting bitten by the numerous mosquitoes. My worst problem, however, was

possibly the fact that I had turned down the Chief of the village on a

previous visit when he had offer his daughter for me to impregnate. Being a hostage would not

be so good once I thought about it. I decided that I wasn’t going to let them get me.

I grabbed the monkey wrench from the side door pocket and climbed back on the left

float. I propped up the cowling access door and reached in banging the starter contactor

as hard as I could.

Once the contactor starts to chatter it eventually welds itself shut. If you banged the

housing you could sometimes free the tack welds and get another start out of it before it

welded itself shut again. I hoped for the best. Troy and the boys had offered help, but

there was really nothing they could do. I closed the cowlings and turned down the float to

get back in and looked right into the bloodshot eyes of a large black Ijaw villager

boarding the float from the rear.

While I had been busy banging aircraft parts silly, the one canoe had sped ahead of the

rest and caught up to our floatplane. I yelled at him, “Get off, I’m starting the engine.

Don’t you get on here.” He paid me no heed and stepped on the float. I could see the

second canoe making its way around to the other side. The Ijaw stepped up to block my

access to the cockpit. I stood still with the monkey wrench in my hand wondering what to

do.

From the first canoe another Ijaw had managed to find the

rear door handle and was opening the door where the two old boys were seated side by side. A third Ijaw climbed on

the float and they each grabbed an arm. They were all

shouting in their native tongue and in broken English, but damned if I could make out

what they were saying. It wasn’t quite like “Death to infidels,” but more like “Prepare to

meet your God Ayibo.”

“Don’t let them in, close the door,” I yelled. I still remember the look on these two guys

faces as they just sat there not doing a thing. They had the look of two resigned sinners

about to meet their maker and attempting to gain quick redemption. Two angels with sad

sorry faces.

Meanwhile, the second canoe had reached the starboard side and boarded the

floats. They too opened the rear door and were wrestling to pull the big boys from their

seats. In the fury no one noticed that they still had on their seat belts and were going

nowhere. Another Ijaw had opened Troy’s door and was tugging on his blue-jeaned leg.

Troy at least was not about to let the intruders from the wooded canoe into his safe haven.

He kicked at the intruder and rapped his knuckles just to let him know he meant business.

I decided it was now or never. I pointed down to the black rubber coated rope that stays

on the float for mooring back at the main base, and made my best “afraid for my life

face” while yelling as loud as I could “snake, snake, you die, snake snake!” The big guy

nearest me immediately jumped a foot high right off his spot and nearly fell in the canoe.

I stepped forward and reached into the plane, flipped on the battery switch and hit the

starter toggle switch. The beautiful turbine started to whine and the prop began to swing

in a slow graceful arch.

That got all their attention. I began to yell for all I was worth, “YOU DIE, YOU DIE,

THE PLANE WILL KILL YOU!” As the “canoe that flew” was still considered bad juju,

the noise and my yelling confused them with dread. They started to step back in fear of

what may happen. I scrambled up onto the pilot-door step and pushed the fuel condition

lever into idle. As soon as the engine caught I pushed in the prop and advanced the high

idle. The beaver’s high idle is 75% Ng so it really began to wind up. The Beaver started

to move with me hanging half out the door.

About then several more canoes had reached the tail and the Ijaws had grabbed the

elevator. I made my way into my seat and jerked the elevator knocking one surprised

fellow in the chin. The prop wash began to blast the riders on the floats and forced the

doors shut. I advanced the power lever ahead and really let them have it.

Wide eyed and confused they fell back into their canoes and my big friend fell right over

the other side into the river. As long as the plane was moving ahead we were safe until

we reached the end of our rope, literally. The anchor reach was quickly playing out. I

pulled the power lever and fuel condition lever into idle and jumped out on the float to

retrieve my anchor. This time the knot came through with a single pull. As I reeled in the

rope I could see my followers making a heroic second effort. There was now 25-30

canoes in the chase. I climbed back in and waited for them to catch up. When I could see

the reds of their eyes I let them have it with both exhaust stacks. I opened up the tap to let

the full force of about 680 hp show them who was boss man.

I let the Turbo-Beaver fly right out of the water without even making the step and then

held 65 knots right to 400 feet. I did not even have to fly the bend. I was gone. Troy was

whooping from his relief and the boys hollered along with him. 50 minutes later I was in

Gordon’s office passing on Lamar’s message. We planned for me to fly to another nearby

work site where I could safely land and to send a flyboat from there with Andy to start

the negotiations. Andy showed up an hour later and I dropped him off at the prearranged

site where the flyboat was waiting.

I was a couple hours before we heard from them, but eventually a call came through on

the HF. It was Lamar. Everybody was fine. A couple of the workers had been

overwhelmed and beaten; one worker had his ear cut off, but otherwise nothing serious. The entire village, however, including

men, women, children, babies and dogs, were all over the equipment. The idea was that

unless we employed the men from the village and paid the Chief a large tribute, they

would simply continue to occupy our work barges and stop the procession from moving

anywhere.

Later Lamar told us

that the damn’est thing he ever saw was the sight of racks of pipes on the

barges filled with babies. The mothers had placed their little bundles of joy in the mouth

of each of the pipes to effect a work stoppage. Lamar said the babies crying in the pipes

was like bullfrogs in culverts, each one competing to see who would be the loudest.

Willbros, the big American pipeline company, had been shutdown by pipe babies.

Later Lamar told us

that the damn’est thing he ever saw was the sight of racks of pipes on the

barges filled with babies. The mothers had placed their little bundles of joy in the mouth

of each of the pipes to effect a work stoppage. Lamar said the babies crying in the pipes

was like bullfrogs in culverts, each one competing to see who would be the loudest.

Willbros, the big American pipeline company, had been shutdown by pipe babies.

I don’t know how the negotiations were settled, but a few days later the work barges were

on the move. I had done a couple of trips moving people and equipment and large bags of

money into the area, being careful each time to meet the flyboat in a safe place. I never

shut down or anchored for sometime, doing all my transfers in feather. “Once bitten” they

say.

After a rough night in the bar, the two good old boys quit and left for home. Troy stayed.

I pored over the maintenance manual until I found a diode that was supposed to stop the

starter contactor from chattering. Tao pulled it out to discover that it had burnt. Without

the diode the contactors would only last a few starts before chattering and consequently

welding shut.

A week after the pipe barges left Apoi Creek, however, a small contingency arrived

from the Ijaw village. The men were dressed in bright woven costumes and shiny bower hats. The women

were bundled in fancy colourful cotton wrappers. They had come to see the “boss man” Lamar.

Apparently one of the ladies had forgotten her baby in a pipe and they had come to get it

back.

Images© by John S Goulet

![]()

An absolutely true Short Story by John S Goulet.

The attitude indicator will guide you back to Inside Africa.

Top of this

page.

Top of this

page.

Last modified on

March 05, 2006 .

© Virtual Horizons, 1996.